The Project Gutenberg eBook, Woman as Decoration, by Emily Burbank

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Woman as Decoration

Author: Emily Burbank

Release Date: July 23, 2006 [eBook #18901]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WOMAN AS DECORATION***

E-text prepared by Audrey Longhurst, Cori Samuel,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net/)

from page images generously made available by

Home Economics Archive: Research, Tradition and History,

Albert R. Mann Library, Cornell University

(http://hearth.library.cornell.edu/)

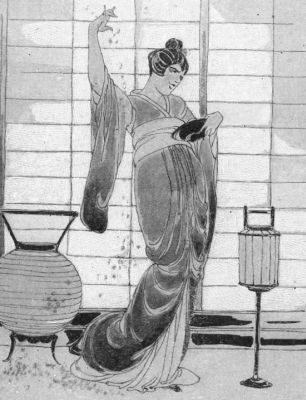

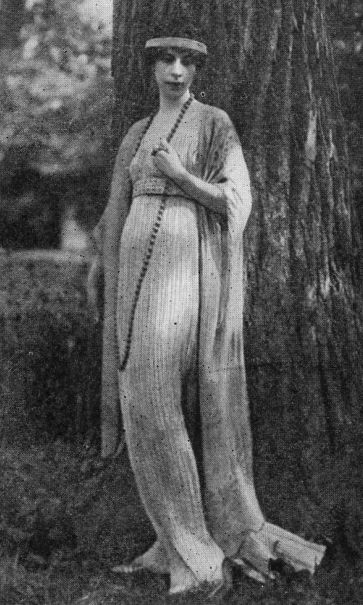

PLATE I

Madame Geraldine Farrar as Thaïs in the opera of that name.

It is a sketch made from life for this book. Observe the

gilded wig and richly embroidered gown. They are after

descriptions of a costume worn by the real Thaïs. It is a

Greek type of costume but not the familiar classic Greek of

sculptured story. Thaïs was a reigning beauty and acted in

the theatre of Alexandria in the early Christian era.

Sketched for "Woman as Decoration" by Thelma Cudlipp

Sketched for "Woman as Decoration" by Thelma Cudlipp

Mme. Geraldine Farrar in Greek Costume as Thaïs

WOMAN AS DECORATION

BY

EMILY BURBANK

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY 1917

Copyright, 1917

By DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY, Inc.

DEDICATED

to

V. B. G.

FOREWORD

Woman as Decoration is intended as a sequel to The Art of

Interior Decoration (Grace Wood and Emily Burbank).

Having assisted in setting the stage for woman, the next logical step is

the consideration of woman, herself, as an important factor in the

decorative scheme of any setting,—the vital spark to animate all

interior decoration, private or public. The book in hand is intended as

a brief guide for the woman who would understand her own type,—make the

most of it, and know how simple a matter it is to be decorative if she

will but master the few rules underlying all successful dressing. As the

costuming of woman is an art, the history of that art must be known—to

a certain extent—by one who would be an intelligent student of our

subject. With the assistance of thirty-three illustrations to throw

light upon the text, we have tried to tell the beguiling story of

decorative woman, as she appears in frescoes and bas reliefs of Ancient

Egypt, on Greek vases, the Gothic woman in tapestry and stained glass,

woman in painting, stucco and tapestry of the Renaissance, seventeenth,

eighteenth and nineteenth century woman in portraits.

Contemporary woman's costume is considered, not as fashion, but as

decorative line and colour, a distinct contribution to the interior

decoration of her own home or other setting. In this department, woman

is given suggestions as to the costuming of herself, beautifully and

appropriately, in the ball-room, at the opera, in her boudoir, sun-room

or on her shaded porch; in her garden; when driving her own car; by the

sea, or on the ice.

Woman as Decoration has been planned, in part, also to fill a need very

generally expressed for a handbook to serve as guide for beginners in

getting up costumes for fancy-dress balls, amateur theatricals, or the

professional stage.

We have tried to shed light upon period costumes and point out ways of

making any costume effective.

Costume books abound, but so far as we know, this is the first attempt

to confine the vast and perplexing subject within the dimensions of a

small, accessible volume devoted to the principles underlying the

planning of all costumes, regardless of period.

The author does not advocate the preening of her feathers as woman's

sole occupation, in any age, much less at this crisis in the making of

world history; but she does lay great emphasis on the fact that a woman

owes it to herself, her family and the public in general, to be as

decorative in any setting, as her knowledge of the art of dressing

admits. This knowledge implies an understanding of line, colour,

fitness, background, and above all, one's own type. To know one's type,

and to have some knowledge of the principles underlying all good

dressing, is of serious economic value; it means a saving of time,

vitality and money.

The watchword of to-day is efficiency, and the keynote to modern

costuming, appropriateness. And so the spirit of the time records itself

in the interesting and charming subdivision of woman's attire.

One may follow Woman Decorative in the Orient on vase, fan, screen and

kakemono; as she struts in the stiff manner of Egyptian bas reliefs,

across walls of ancient ruins, or sits in angular serenity, gazing into

the future through the narrow slits of Egyptian eyes, oblivious of time;

woman, beautiful in the European sense, and decorative to the

superlative degree, on Greek vase and sculptured wall. Here in rhythmic

curves, she dandles lovely Cupid on her toe; serves as vestal virgin at

a woodland shrine; wears the bronze helmet of Minerva; makes laws, or as

Penelope, the wife, wearily awaits her roving lord. She moves in august

majesty, a sore-tried queen, and leaps in merry laughter as a care-free

slave; pipes, sings and plies the distaff. Sauntering on, down through

Gothic Europe, Tudor England, the adolescent Renaissance, Bourbon

France, into the picturesque changes of the eighteenth century, we ask,

can one possibly escape our theme—Woman as Decoration? No, for she is

carved in wood and stone; as Mother of God and Queen of Heaven gleams in

the jeweled windows of the church, looks down in placid serenity on

lighted altar; is woven in tapestry, in fact dominates all art,

painting, stucco or marble, throughout the ages.

If one would know the story of Woman's evolution and retrogression—that

rising and falling tide in civilisation—we commend a study of her as

she is presented in Art. A knowledge of her costume frequently throws

light upon her age; a thorough knowledge of her age will throw light

upon her costume.

A study of the essentials of any costume, of any period, trains the eye

and mind to be expert in planning costumes for every-day use. One learns

quickly to discriminate between details which are ornaments, because

they have meaning, and those which are only illiterate superfluities;

and one learns to master many other points.

It is not within the province of this book to dwell at length upon

national costume, but rather to follow costume as it developed with and

reflected caste, after human society ceased to be all alike as to

occupation, diversion and interest.

In the world of caste, costume has gradually evolved until it aims

through appropriateness, at assisting woman to fulfil her rôle. With

peasants who know only the traditional costume of their province, the

task must often be done in spite of the costume, which is picturesque or

grotesque, inconvenient, even impossible; but long may it linger to

divert the eye! Russia, Germany, France, Spain, Italy, Poland,

Scandinavia,—all have an endless variety of costumes, rich in souvenirs

of folk history, rainbows of colour and bizarre in line, but it is

costuming the woman of fashion which claims our attention.

The succeeding chapters will treat of woman, the vital spark which gives

meaning to any setting—indoors, out of doors, at the opera, in the

ball-room, on the ice—where you will. Each chapter has to do with

modern woman and the historical paragraphs are given primarily to shed

light upon her costume.

It is shown that woman's decorative appearance affects her psychology,

and that woman's psychology affects her decorative appearance.

Some chapters may, at first glance, seem irrelevant, but those who have

seriously studied any art, and then undertaken to tell its story

briefly in simple, direct language, with the hope of quickly putting

audience or reader in touch with the vital links in the chain of

evidence, will understand the author's claim that no detour which

illustrates the subject can in justice be termed irrelevant. In the

detours often lie invaluable data, for one with a mind for

research—whether author or reader. This is especially true in

connection with our present task, which involves unravelling some of the

threads from the tangled skein of religion, dancing, music, sculpture

and painting—that mass of bright and sombre colour, of gold and silver

threads, strung with pearls and glittering gems strangely broken by

age—which tells the epic-lyric tale of civilisation.

While we state that it is not our aim to make a point of fashion as

such, some of our illustrations show contemporary woman as she appears

in our homes, on our streets, at the play, in her garden, etc. We have

taken examples of women's costumes which are pre-eminently

characteristic of the moment in which we write, and as we believe,

illustrate those laws upon which we base our deductions concerning

woman as decoration. These laws are: appropriateness of her costume to

the occasion; consideration of the type of wearer; background against

which costume is to be worn; and all decoration (which includes jewels),

as detail with raison d'être. The body should be carried with form (in

the sporting sense), to assist in giving line to the costume.

The chic woman is the one who understands the art of elimination in

costumes. Wear your costumes with conviction—by which we mean decide

what picture you will make of yourself, make it and then enjoy it! It is

only by letting your personality animate your costume that you make

yourself superior to the lay figure or the sawdust doll.

CONTENTS

| I | A Few Hints for the Novice who Would Plan Her Costumes | 1 |

| | Rules having economic value while aiming at

decorativeness.—Lines and colouring emphasised

or modified by costuming.—Temperaments affect

carriage of the body.—Line of body affects

costume.—Technique of controlling the physique.—The

highly sensitised woman.—Costuming an

art.—Studying types.—Starring one's own good

points.—Beauty not so fleeting as is supposed

if costume is adapted to its changing aspects.—Masters

in art of costuming often discover and

star previously unrecognised beauty.—Establishing

the habit of those lines and colours in

gowns, hats, gloves, parasols, sticks, fans and

jewels which are your own.—The intelligent

purchaser.—The best dressed women.—Value of

understanding one's background.—Learning the

art of understanding one's background.—Learning

the art of costuming from masters of the

art.—How to proceed with this study.—Successful

costuming not dependent upon amount of

money spent upon it.—An example | |

| | | |

| II | The Laws Underlying All Costuming of Woman | 23 |

| | Appropriateness keynote of costuming to-day.—Five

salient points to be borne in mind when

planning a costume.—Where English, French,

and American women excel in art of costuming.—Feeling

for line.—To make our points clear

constant reference to the stage is necessary.—Bakst

and Poiret.—Turning to the Orient for

line and colour.—Keeping costume in same key

as its settings.—How to know your period; its

line, colours and characteristic details.—Studying

costumes in Gothic illuminations | |

| | | |

| III | How to Dress Your Type | 46 |

| | A Few Points Applying to all Costumes.—Background.—Line

and colour of costumes to

bring out the individuality of wearer.—The chic

woman defined.—Intelligent expressing of self

in mise-en-scène.—Selecting one's colour scheme | |

| | | |

| IV | The Psychology of Clothes | 54 |

| | Effect of clothes upon manners.—The natural

instinct for costuming, "clothes sense."—Costuming

affecting psychology of wearer.—Clothes

may liberate or shackle the spirit of women, be

a tyrant or magician's wand.—Follow colour

instinct in clothes as well as housefurnishings | |

| | | |

| V | Establish Habits of Carriage Which Create Good Line | 66 |

| | Woman's line result of habits of a mind controlled

by observations, conventions, experiences

and attitudes which make her personality.—Training

lines of physique from childhood; an

example.—A knowledge of how to dress appropriately

leads to efficiency | |

| | | |

| VI | Colour In Woman's Costume | 74 |

| | Colour hall-mark of to-day.—Bakst, Rheinhardt

and Granville Barker, teachers of the new

colour vocabulary.—PORTABLE BACKGROUNDS | |

| | | |

| VII | Footwear | 85 |

| | Importance of carefully considering extremities.—What

constitutes a costume.—Importance

of learning how to buy, put on and wear each

detail of costume if one would be a decorative picture.—Spats.—Stockings.—Slippers.—Buckles | |

| | | |

| VIII | Jewelry as Decoration | 94 |

| | Considered as colour and line not with regard

to intrinsic worth.—To complete a costume or

furnish keynote upon which to build a costume.—Distinguished

jewels with historic associations

worn artistically; examples.—Know what

jewels are your affair as to colour, size, and

shape.—To know what one can and cannot

wear in all departments of costuming prepares

one to grasp and make use of expert suggestions.

How fashions come into being.—One of the rules

as to how jewels should be worn.—Gems and

paste | |

| | | |

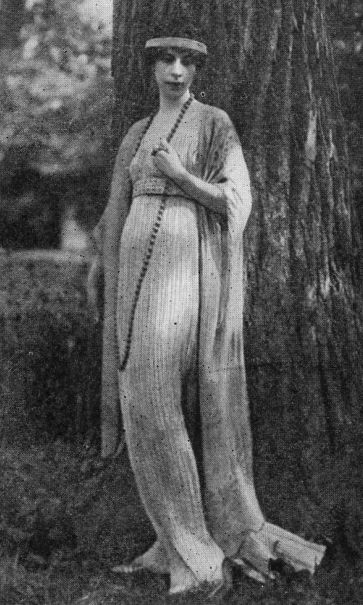

| IX | Woman Decorative in Her Boudoir | 111 |

| | Negligée or tea-gown belongs to this intimate

setting.—Fortuny the artist designer of tea-gowns.—Sibyl

Sanderson.—The decorative value

of a long string of beads.—Beauty which is the

result of conscious effort.—Bien soiné a hall-mark

of our period | |

| | | |

| X | Woman Decorative in Her Sun-Room | 116 |

| | Since a winter sun-room is planned to give

the illusion of summer, one's costuming for it

should carry out the same idea.—The sun-room

provides a means for using up last summer's

costumes.—The hat, if worn, should suggest

repose, not action.—The age and habits of those

occupying a sun-room dictate the exact type

of costume to be worn.—Colour scheme | |

| | | |

| XI | I. Woman Decorative in Her Garden | 124 |

| | In the garden the costume should have a

decorative outline but simple colour scheme

which harmonises with background of flowers.—White,

grey, or one note of colour preferable.—The

flowers furnish variety and colour.—Lady

de Bathe (Mrs. Langtry) in her garden

at Newmarket, England | |

| | | |

| | II. Woman Decorative on the Lawn | |

| | One may be a flower or a bunch of flowers

for colour against the unbroken sweep of green

underfoot and background of shrubs and trees.—Chic

outline and interesting detail, as well as

colour, of distinct value in a costume for lawn.—How

to cultivate an unerring instinct for

what is a successful costume for any given occasion | |

| | | |

| | III. Woman Decorative on the Beach | |

| | If one would be a contribution to the picture,

figure as white or vivid colour on beach,

deck of steamer or yacht | |

| | | |

| XII | Woman As Decoration When Skating | 134 |

| | Line of the body all important.—The necessity

of mastering form to gain efficiency in any

line; examples.—The traditional skating costume

has the lead | |

| | | |

| XIII | Woman Decorative in Her Motor Car | 145 |

| | The colour of one's car inside and out important

factor in effect produced by one's carefully

chosen costume | |

| | | |

| XIV | How To Go About Planning A Period Costume | 154 |

| | Period.—Background.—Outline.—Materials.—Colour

scheme.—Detail with meaning.—Authorities.—Consulting

portraits by great masters.—Geraldine

Farrar.—Distinguished collection of

costume plates.—One result of planning period

costumes is the opening up of vistas in history.—Every

detail of a period costume has its fascinating

story worth the knowing.—Brief historic

outline to serve as key to the rich storehouse

of important volumes on costumes and

the distinguished textless books of costume

plates.—Period of fashions in costumes developing

without nationality.—Nationality declared

in artistry of workmanship and the modification

or exaggeration of an essential detail according

to national or individual temperament.—Evolution

of woman's costume.—Assyria.—Egypt.—Byzantium.—Greece.—Rome.—Gothic

Europe.—Europe of the

Renaissance,—seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth

century through Mid-Victorian period.—Cord tied about

waist origin of costumes for women and men | |

| | | |

XV

| The Story Of Period Costumes

A Résumé | 172 |

| | Woman as seen in Egyptian sculpture-relief;

on Greek vase; in Gothic stained glass; carved

stone; tapestry; stucco; and painting of the

Renaissance; eighteenth and nineteenth century

portraits.—Art throughout the ages reflects

woman in every rôle; as companion, ruler,

slave, saint, plaything, teacher, and voluntary

worker.—Evolution of outline of woman's costume,

including change in neck; shoulder;

evolution of sleeve; girdle; hair; head-dress;

waist line; petticoat.—Gradual disappearance

of long, flowing lines characteristic of Greek

and Gothic periods.—Demoralisation of Nature's

shoulder and hip-line culminates in the Velasquez

edition of Spanish fashion and the Marie

Antoinette extravaganzas | |

| | | |

| XVI | Development Of Gothic Costume | 192 |

| | Gothic outline first seen as early as fourth

century.—Costume of Roman-Christian women.—Ninth

century.—The Gothic cape of twelfth,

thirteenth and fourteenth centuries made

familiar on the Virgin and saints in sacred

art.—The tunic.—Restraint in line, colour, and

detail gradually disappear with increased circulation

of wealth until in fifteenth century we

see humanity over-weighted with rich brocades,

laces, massive jewels, etc.

The Virgin in Art

Late Middle Ages.—Sovereignty of the Virgin

as explained in "The Cathedrals of Mont St.

Michel and Chartres," by Henry Adams.—Woman

as the Virgin dominates art of twelfth,

thirteenth, and fourteenth centuries.—The girdle.—The

round neck.—The necklace, etc. | |

| | | |

XVII

| The Renaissance

Sixteenth And Seventeenth Centuries | 214 |

| | Pointed and other head-dresses with floating

veils.—Neck low off shoulders.—Skirts part as

waist-line over petticoat.—Wealth of Roman

Empire through new trade channels had led to

importation of richly coloured Oriental stuffs.—Same

wealth led to establishing looms in

Europe.—Clothes of man like his over-ornate

furniture show debauched and vulgar taste.—The

good Gothic lines live on in costumes of

nuns and priests.—The Davanzati Palace collection,

Florence, Italy.—Long pointed shoes

of the Middle Ages give way to broad square

ones.—Gorgeous materials.—Hats.—Hair.—Sleeves.—Skirts.—Crinolines.—Coats.—Overskirts

draped to develop into panniers of Marie

Antoinette's time.—Directoire reaction to simple

lines and materials | |

| | | |

| XVIII | Eighteenth Century | 233 |

| | Political upheavals.—Scientific discoveries.—Mechanical

inventions.—Chemical achievements.—Chintz

or stamped linens of Jouy near Versailles.—Painted

wall-papers after the Chinese.—Simplicity

in costuming of woman and man | |

| | | |

| XIX | Woman In The Victorian Period | 241 |

| | First seventy years of nineteenth century.—"Historic

Dress in America" by Elizabeth McClellan.—Hoops,

wigs, absurdly furbished head-dresses,

paper-soled shoes, bonnets enormous,

laces of cobweb, shawls from India, rouge and

hair-grease, patches and powder, laced waists,

and "vapours."—Man still decorative | |

| | | |

| XX | Sex In Costuming | 244 |

| | "European dress."—Progenitor of costume

worn by modern men.—The time when no distinction

was made between materials used for

man and woman.—Velvets, silks, satins, laces,

elaborate cuffs and collars, embroidery, jewels

and plumes as much his as hers | |

| | | |

| XXI | Line And Colour Of Costumes In Hungary | 252 |

| | In a sense colour a sign of virility.—Examples.—Studying

line and colour in Magyar

Land.—In Krakau, Poland,—A highly decorative

Polish peasant and her setting | |

| | | |

| XXII | Studying Line and Colour in Russia | 265 |

| | Kiev our headquarters.—Slav temperament

an integral part of Russian nature expressed

in costuming as well as folk songs and dances

of the people.—Russian woman of the fashionable

world.—The Russian pilgrims as we saw

them tramping over the frozen roads to the

shrines of Kiev, the Holy City and ancient

capital of Russia at the close of the Lenten

season.—Their costumes and their psychology | |

| | | |

| XXIII | Mark Twain's Love of Colour in all Costuming | 276 |

| | Wrapped in a crimson silk dressing-gown

on a balcony of his Italian villa in Connecticut,

Mark Twain dilated on the value of brilliant

colour in man's costuming.—His creative,

picturing-making mind in action.—Other themes

followed | |

| | | |

| XXIV | The Artist And His Costume | 283 |

| | A God-given sense of the beautiful.—The

artist nature has always assumed poetic license

in the matter of dress.—Many so-called affectations

have raison d'être.—Responding to texture,

colour and line as some do to music and

scenery.—How Japanese actors train themselves

to act women's parts by wearing woman's

costumes off the stage.—This cultivates the required

feeling for the costumes.—The woman

devotee to sports when costumed.—Richard

Wagner's responsiveness to colour and texture.—Clyde

Fitch's sensitiveness to the same.—The

wearing of jewels by men.—King Edward

VII.—A remarkable topaz worn by a Spaniard.—Its

undoing as a decorative object through

its resetting | |

| | | |

| XXV | Idiosyncrasies in Costume | 292 |

| | Fashions in dress all powerful because they

seize upon the public mind.—They become the

symbol of manners and affect human psychology.—Affectations

of the youth of Athens.—Les

Merveilleux, Les Encroyables, the Illuminati.—Schiller

during the Storm and Stress

Period.—Venetian belles of the sixteenth century.—The

Cavalier Servente of the seventeenth

century.—Mme. Récamier scandalised London

in eighteenth century by appearing costumed

à la Greque.—Mme. Jerome Bonaparte, a Baltimore

belle, followed suit in Philadelphia.—Hour-glass

waist-line and attendant "vapours"

were thought to be in the rôle of a high-born

Victorian miss.—Appropriateness the contribution

of our day to the story of woman's costuming | |

| | | |

| XXVI | Nationality In Costume | 296 |

| | When seen with perspective the costumes of

various periods appear as distinct types though

to the man or woman of any particular period

the variations of the type are bewildering and

misleading.—Having followed the evolution of

the costume of woman of fashion which comes

under the general head of European dress, before

closing we turn to quite another field, that

of national costumes.—Progress levels national

differences, therefore the student must make the

most of opportunities to observe.—Experiences

in Hungary | |

| | | |

| XXVII | Models | 306 |

| | Historical interest attaches to fashions in

woman's costuming.—One of the missions of

art is to make subtle the obvious.—Examples as

seen in 1917 | |

| | | |

| XXVIII | Woman Costumed for Her War Job | 313 |

| | The Pageant of Life shows that woman has

played opposite man with consistency and success

throughout the ages.—Apropos of this, we

quote from Philadelphia Public Ledger, for

March 25, 1917, an impression of a woman of

to-day costumed appropriately to get efficiency

in her war work | |

| | | |

| | In Conclusion | 324 |

| | A brief review of the chief points to be kept

in mind by those interested in the costuming

of woman so that she figures as a decorative

contribution to any setting | |

| | | |

ILLUSTRATIONS

| I | Mme. Geraldine Farrar in Greek Costume as Thaïs

Sketched by Thelma Cudlipp | (Frontispiece) |

| II | Woman in Ancient Egyptian Sculpture-Relief | 9 |

| III | Woman in Greek Art | 19 |

| IV | Woman on Greek Vase | 29 |

| V | Woman in Gothic Art

Portrait Showing Pointed Head-dress | 39 |

| VI | Woman in Art of the Renaissance

Sculpture-relief in Terra-cotta: The Virgin | 49 |

| VII | Woman in Art of the Renaissance

Sculpture-relief in Terra-cotta: Holy Women | 59 |

| VIII | Tudor England

Portrait of Queen Elizabeth | 69 |

| IX | Spain--Velasquez Portrait | 79 |

| X | Eighteenth Century England

Portrait by Thomas Gainsborough | 89 |

| XI | Bourbon France

Portrait of Marie Antoinette by Madame Vigée Le Brun | 99 |

| XII | Costume of Empire Period

An English Portrait | 109 |

| XIII | Eighteenth Century Costume

Portrait by Gilbert Stuart | 119 |

| XIV | Victorian Period (About 1840)

Mme. Adeline Genée in Costume | 129 |

| XV | Late Nineteenth Century (About 1890)

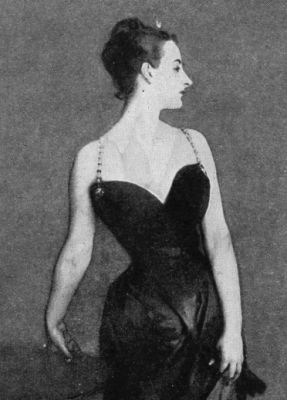

A Portrait by John S. Sargent | 139 |

| XVI | A Modern Portrait

By John W. Alexander | 149 |

| XVII | A Portrait of Mrs. Philip M. Lydig

By I. Zuloaga | 159 |

| XVIII | Mrs. Langtry (Lady de Bathe) in Evening Wrap | 169 |

| XIX | Mrs. Condé Nast in Street Dress

Photograph by Baron de Meyer | 179 |

| XX | Mrs. Condé Nast in Evening Dress | 189 |

| XXI | Mrs. Condé Nast in Garden Costume | 199 |

| XXII | Mrs. Condé Nast in Fortuny Tea Gown | 209 |

| XXIII | Mrs. Vernon Castle in Ball Costume | 219 |

| XXIV | Mrs. Vernon Castle in Afternoon Costume--Winter | 229 |

| XXV | Mrs. Vernon Castle in Afternoon Costume--Summer | 239 |

| XXVI | Mrs. Vernon Castle Costumed À La Guerre for a Walk | 249 |

| XXVII | Mrs. Vernon Castle--A Fantasy | 259 |

| XXVIII | Modern Skating Costume--1917

Winner of Amateur Championship of Fancy Skating | 269 |

| XXIX A | Modern Silhouette--1917

Tailor-Made. Drawn from Life by Elisabeth Searcy | 279 |

| XXX | Tappé's Creations

Sketched for Woman as Decoration by Thelma Cudlipp | 289 |

| XXXI | Miss Elsie De Wolfe in Costume of Red Cross Nurse | 299 |

| XXXII | Mme. Geraldine Farrar in Spanish Costume as Carmen

From Photograph by Courtesy of Vanity Fair | 309 |

| XXXIII | Mme. Geraldine Farrar in Japanese Costume as Madame Butterfly

Sketched by Thelma Cudlipp | 319 |

"The Communion of men upon earth abhors identity more than

nature does a vacuum. Nothing so shocks and repels the

living soul as a row of exactly similar things, whether it

consists of modern houses or of modern people, and nothing

so delights and edifies as distinction."

Coventry Patmore.

"Whatever piece of dress conceals a woman's figure, is

bound, in justice, to do so in a picturesque way."

From an Early Victorian Fashion Paper.

"When was that 'simple time of our fathers' when people were

too sensible to care for fashions? It certainly was before

the Pharaohs, and perhaps before the Glacial Epoch."

W. G. Sumner, in Folkways.

CHAPTER I

A FEW HINTS FOR THE NOVICE WHO WOULD PLAN HER COSTUMES

HERE

are a few rules with regard to the costuming of woman which if

understood put one a long way on the road toward that desirable

goal—decorativeness, and have economic value as well. They are simple

rules deduced by those who have made a study of woman's lines and

colouring, and how to emphasise or modify them by dress.

HERE

are a few rules with regard to the costuming of woman which if

understood put one a long way on the road toward that desirable

goal—decorativeness, and have economic value as well. They are simple

rules deduced by those who have made a study of woman's lines and

colouring, and how to emphasise or modify them by dress.

Temperaments are seriously considered by experts in this art, for the

carriage of a woman and her manner of wearing her clothes depends in

part upon her temperament. Some women instinctively feel line and are

graceful in consequence, as we have said, but where one is not born

with this instinct, it is possible to become so thoroughly schooled in

the technique of controlling the physique—poise of the body, carriage

of the head, movement of the limbs, use of feet and hands, that a sense

of line is acquired. Study portraits by great masters, the movements of

those on the stage, the carriage and positions natural to graceful

women. A graceful woman is invariably a woman highly sensitised, but

remember that "alive to the finger tips"—or toe tips, may be true of

the woman with few gestures, a quiet voice and measured words, as well

as the intensely active type.

The highly sensitised woman is the one who will wear her clothes with

individuality, whether she be rounded or slender. To dress well is an

art, and requires concentration as any other art does. You know the old

story of the boy, who when asked why his necktie was always more neatly

tied than those of his companions, answered: "I put my whole mind on

it." There you have it! The woman who puts her whole mind on the

costuming of herself is naturally going to look better than the woman

who does not, and having carefully studied her type, she will know her

strong points and her weak ones, and by accentuating the former, draw

attention from the latter. There is a great difference, however, between

concentrating on dress until an effect is achieved, and then turning the

mind to other subjects, and that tiresome dawdling, indefinite,

fruitless way, to arrive at no convictions. This variety of woman never

gets dress off her chest.

The catechism of good dressing might be given in some such form as this:

Are you fat? If so, never try to look thin by compressing your figure or

confining your clothes in such a way as to clearly outline the figure.

Take a chance from your size. Aim at long lines, and what dressmakers

call an "easy fit," and the use of solid colours. Stripes, checks,

plaids, spots and figures of any kind draw attention to dimensions; a

very fat woman looks larger if her surface is marked off into many

spaces. Likewise a very thin woman looks thinner if her body on the

imagination of the public subtracting is marked off into spaces

absurdly few in number. A beautifully proportioned and rounded figure

is the one to indulge in striped, checked, spotted or flowered materials

or any parti-coloured costumes.

Never try to make a thin woman look anything but thin. Often by

accentuating her thinness, a woman can make an effect as type, which

gives her distinction. If she were foolish enough to try to look fatter,

her lines would be lost without attaining the contour of the rounded

type. There are of course fashions in types; pale ash blonds, red-haired

types (auburn or golden red with shell pink complexions), dark haired

types with pale white skin, etc., and fashions in figures are as many

and as fleeting.

Artists are sometimes responsible for these vogues. One hears of the

Rubens type, or the Sir Joshua Reynolds, Hauptner, Burne-Jones, Greuse,

Henner, Zuloaga, and others. The artist selects the type and paints it,

the attention of the public is attracted to it and thereafter singles it

out. We may prefer soft, round blonds with dimpled smiles, but that does

not mean that such indisputable loveliness can challenge the

attractions of a slender serpentine tragedy-queen, if the latter has

established the vogue of her type through the medium of the stage or

painter's brush.

A woman well known in the world of fashion both sides of the Atlantic,

slender and very tall, has at times deliberately increased that height

with a small high-crowned hat, surmounted by a still higher feather. She

attained distinction without becoming a caricature, by reason of her

obvious breeding and reserve. Here is an important point. A woman of

quiet and what we call conservative type, can afford to wear conspicuous

clothes if she wishes, whereas a conspicuous type must be reserved in

her dress. By following this rule the overblown rose often makes herself

beautiful. Study all types of woman. Beauty is a wonderful and precious

thing, and not so fleeting either as one is told. The point is, to take

note, not of beauty's departure, but its gradually changing aspect, and

adapt costume, line and colour, to the demands of each year's

alterations in the individual. Make the most of grey hair; as you lose

your colour, soften your tones.

Always star your points. If you happen to have an unusual amount of

hair, make it count, even though the fashion be to wear but little. We

recall the beautiful and unique Madame X. of Paris, blessed by the gods

with hair like bronze, heavy, long, silken and straight. She wore it

wrapped about her head and finally coiled into a French twist on the

top, the effect closely resembling an old Roman helmet. This was design,

not chance, and her well-modeled features were the sort to stand the

severe coiffure, Madame's husband, always at her side that season on

Lake Lucerne, was curator of the Louvre. We often wondered whether the

idea was his or hers. She invariably wore white, not a note of colour,

save her hair; even her well-bred fox terrier was snowy white.

Worth has given distinction to more than one woman by recognising her

possibilities, if kept to white, black, greys and mauves. A beautiful

Englishwoman dressed by this establishment, always a marked figure at

whatever embassy her husband happens to be posted, has never been seen

wearing anything in the evening but black, or white, with very simple

lines, cut low and having a narrow train.

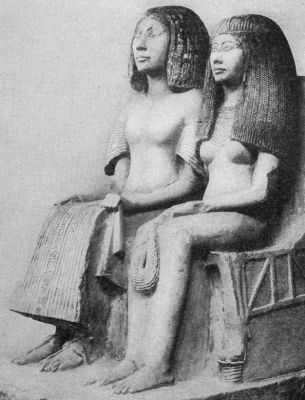

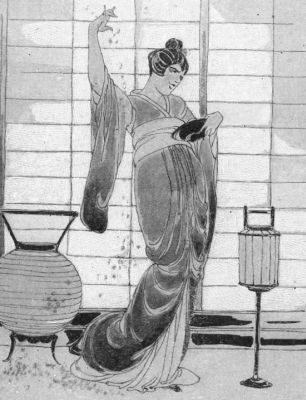

PLATE II

Woman in ancient Egyptian sculpture-relief about 1000

B.C.

We have here a husband and wife. (Metropolitan Museum.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Woman in Ancient Egyptian

Sculpture-Relief

It may take courage on the part of dressmaker, as well as the woman in

question, but granted you have a distinct style of your own, and

understand it, it is the part of wisdom to establish the habit of those

lines and colours which are yours, and then to avoid experiments with

outré lines and shades. They are almost sure to prove failures. Taking

on a colour and its variants is an economic, as well as an artistic

measure. Some women have so systematised their costuming in order to be

decorative, at the least possible expenditure of vitality and time

(these are the women who dress to live, not live to dress), that they

know at a glance, if dress materials, hats, gloves, jewels, colour of

stones and style of setting, are for them. It is really a joy to shop

with this kind of woman. She has definitely fixed in her mind the

colours and lines of her rooms, all her habitual settings, and the

clothes and accessories best for her. And with the eye of an artist,

she passes swiftly by the most alluring bargains, calculated to

undermine firm resolution. In fact one should not say that this woman

shops; she buys. What is more, she never wastes money, though she may

spend it lavishly.

Some of the best dressed women (by which we always mean women dressed

fittingly for the occasion, and with reference to their own particular

types) are those with decidedly limited incomes.

There are women who suggest chiffon and others brocade; women who call

for satin, and others for silk; women for sheer muslins, and others for

heavy linen weaves; women for straight brims, and others for those that

droop; women for leghorns, and those they do not suit; women for white

furs, and others for tawny shades. A woman with red in her hair is the

one to wear red fox.

If you cannot see for yourself what line and colour do to you, surely

you have some friend who can tell you. In any case, there is always the

possibility of paying an expert for advice. Allow yourself to be guided

in the reaching of some decision about yourself and your limitations, as

well as possibilities. You will by this means increase your

decorativeness, and what is of more serious importance, your economic

value.

A marked example of woman decorative was seen on the recent occasion

when Miss Isadora Duncan danced at the Metropolitan Opera House, for the

benefit of French artists and their families, victims of the present

war. Miss Duncan was herself so marvelous that afternoon, as she poured

her art, aglow and vibrant with genius, into the mould of one classic

pose after another, that most of her audience had little interest in any

other personality, or effect. Some of us, however, when scanning the

house between the acts, had our attention caught and held by a

charmingly decorative woman occupying one of the boxes, a quaint outline

in silver-grey taffeta, exactly matching the shade of the woman's hair,

which was cut in Florentine fashion forming an aureole about her small

head,—a becoming frame for her fine, highly sensitive face. The deep

red curtains and upholstery in the box threw her into relief, a lovely

miniature, as seen from a distance. There were no doubt other charming

costumes in the boxes and stalls that afternoon, but none so successful

in registering a distinct decorative effect. The one we refer to was

suitable, becoming, individual, and reflected personality in a way to

indicate an extraordinary sensitiveness to values, that subtle instinct

which makes the artist.

With very young women it is easy to be decorative under most conditions.

Almost all of them are decorative, as seen in our present fashions, but

to produce an effect in an opera box is to understand the carrying

power of colour and line. The woman in the opera box has the same

problem to solve as the woman on the stage: her costume must be

effective at a distance. Such a costume may be white, black and any

colour; gold, silver, steel or jet; lace, chiffon—what you

will—provided the fact be kept in mind that your outline be striking

and the colour an agreeable contrast against the lining of the box.

Here, outline is of chief importance, the silhouette must be definite;

hair, ornaments, fan, cut of gown, calculated to register against the

background. In the stalls, colour and outline of any single costume

become a part of the mass of colour and black and white of the audience.

It is difficult to be a decorative factor under these conditions, yet

we can all recall women of every age, who so costume themselves as to

make an artistic, memorable impression, not only when entering opera,

theatre or concert hall, but when seated. These are the women who

understand the value of elimination, restraint, colour harmony and that

chic which results in part from faultless grooming. To-day it is not

enough to possess hair which curls ideally: it must, willy nilly, curl

conventionally!

If it is necessary, prudent or wise that your purchases for each season

include not more than six new gowns, take the advice of an actress of

international reputation, who is famous for her good dressing in private

life, and make a point of adding one new gown to each of the six

departments of your wardrobe. Then have the cleverness to appear in

these costumes whenever on view, making what you have fill in between

times.

To be clear, we would say, try always to begin a season with one

distinguished evening gown, one smart tailor suit, one charming house

gown, one tea gown, one negligée and one sport suit. If you are needing

many dancing frocks, which have hard wear, get a simple, becoming

model, which your little dressmaker, seamstress or maid can copy in

inexpensive but becoming colours. You can do this in Summer and Winter

alike, and with dancing frocks, tea gowns, negligées and even sport

suits. That is, if you have smart, up-to-date models to copy.

One woman we know bought the finest quality jersey cloth by the yard,

and had a little dressmaker copy exactly a very expensive skirt and

sweater. It seems incredible, but she saved on a ready made suit exactly

like it forty dollars, and on one made to measure by an exclusive house,

one hundred dollars! Remember, however, that there was an artist back of

it all and someone had to pay for that perfect model, to start with. In

the case we cite, the woman had herself bought the original sport suit

from an importer who is always in advance with Paris models.

If you cannot buy the designs and workmanship of artists, take advantage

of all opportunities to see them; hats and gowns shown at openings, or

when your richer friends are ordering. In this way you will get ideas to

make use of and you will avoid looking home-made, than which, no more

damning phrase can be applied to any costume. As a matter of fact it

implies a hat or gown lacking an artist's touch and describes many a one

turned out by long-established and largely patronised firms.

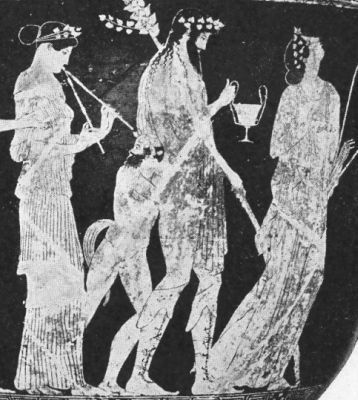

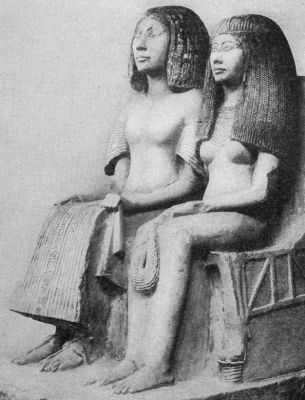

PLATE III

A Greek vase. Dionysiac scenes about 460 B.C.

Interesting costumes. (Metropolitan Museum.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Woman on Greek Vase

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Woman on Greek Vase

The only satisfactory copy of a Fortuny tea gown we have ever seen

accomplished away from the supervision of Fortuny himself, was the

exquisite hand-work of a young American woman who lives in New York, and

makes her own gowns and hats, because her interest and talent happen to

be in that direction. She told a group of friends the other day, to whom

she was showing a dainty chiffon gown, posed on a form, that to her, the

planning and making of a lovely costume had the same thrilling

excitement that the painting of a picture had for the artist in the

field of paint and canvas. This same young woman has worked constantly

since the European war began, both in London and New York, on the

shapeless surgical shirts used by the wounded soldiers. In this, does

she outrank her less accomplished sisters? Yes, for the technique she

has achieved by making her own costumes makes her swift and economical,

both in the cutting of her material and in the actual sewing and she is

invaluable as a buyer of materials.

CHAPTER II

THE LAWS UNDERLYING ALL COSTUMING OF WOMAN

HAT

every costume is either right or wrong is not a matter of general

knowledge. "It will do," or "It is near enough" are verdicts responsible

for beauty hidden and interest destroyed. Who has not witnessed the mad

mental confusion of women and men put to it to decide upon costumes for

some fancy-dress ball, and the appalling ignorance displayed when, at

the costumer's, they vaguely grope among battered-looking garments,

accepting those proffered, not really knowing how the costume they ask

for should look?

HAT

every costume is either right or wrong is not a matter of general

knowledge. "It will do," or "It is near enough" are verdicts responsible

for beauty hidden and interest destroyed. Who has not witnessed the mad

mental confusion of women and men put to it to decide upon costumes for

some fancy-dress ball, and the appalling ignorance displayed when, at

the costumer's, they vaguely grope among battered-looking garments,

accepting those proffered, not really knowing how the costume they ask

for should look?

Absurd mistakes in period costumes are to be taken more or less

seriously according to temperament. But where is the fair woman who will

say that a failure to emerge from a dressmaker's hands in a successful

costume is not a tragedy? Yet we know that the average woman, more

often than not, stands stupefied before the infinite variety of

materials and colours of our twentieth century, and unless guided by an

expert, rarely presents the figure, chez-elle, or when on view in

public places, which she would or could, if in possession of the few

rules underlying all successful dressing, whatever the century or

circumstances.

Six salient points are to be borne in mind when planning a costume,

whether for a fancy-dress ball or to be worn as one goes about one's

daily life:

First, appropriateness to occasion, station and age;

Second, character of background you are to appear against (your

setting);

Third, what outline you wish to present to observers (the period of

costume);

Fourth, what materials of those in use during period selected you will

choose;

Fifth, what colours of those characteristic of period you will use;

Sixth, the distinction between those details which are obvious

contributions to the costume, and those which are superfluous, because

meaningless or line-destroying.

Let us remind our reader that the woman who dresses in perfect taste

often spends far less money than she who has contracted the habit of

indefiniteness as to what she wants, what she should want, and how to

wear what she gets.

Where one woman has used her mind and learned beyond all wavering what

she can and what she cannot wear, thousands fill the streets by day and

places of amusement by night, who blithely carry upon their persons

costumes which hide their good points and accentuate their bad ones.

The rara avis among women is she who always presents a fashionable

outline, but so subtly adapted to her own type that the impression made

is one of distinct individuality.

One knows very well how little the average costume counts in a theatre,

opera house or ball-room. It is a question of background again. Also you

will observe that the costume which counts most individually, is the one

in a key higher or lower than the average, as with a voice in a crowded

room.

The chief contribution of our day to the art of making woman decorative

is the quality of appropriateness. I refer of course to the woman who

lives her life in the meshes of civilisation. We have defined the smart

woman as she who wears the costume best suited to each occasion when

that occasion presents itself. Accepting this definition, we must all

agree that beyond question the smartest women, as a nation, are English

women, who are so fundamentally convinced as to the invincible law of

appropriateness that from the cradle to the grave, with them evening

means an evening gown; country clothes are suited to country uses and a

tea-gown is not a bedroom negligée. Not even in Rome can they be

prevailed upon "to do as the Romans do."

Apropos of this we recall an experience in Scotland. A house party had

gathered for the shooting,—English men and women. Among the guests were

two Americans; done to a turn by Redfern. It really turned out to be a

tragedy, as they saw it, for though their cloth skirts were short, they

were silk-lined; outing shirts were of crêpe—not flannel; tan boots,

but thinly soled; hats most chic, but the sort that drooped in a mist.

Well, those two American girls had to choose between long days alone,

while the rest tramped the moors, or to being togged out in borrowed

tweeds, flannel shirts and thick-soled boots.

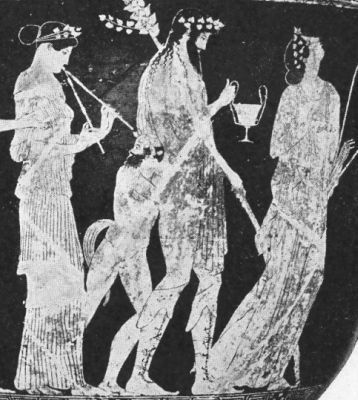

PLATE IV

Greek Kylix. Signed by Hieron, about 400 B.C.

Athenian. The woman wears one of the gowns Fortuny (Paris)

has reproduced as a modern tea gown. It is in two pieces.

The characteristic short tunic reaches just below waist line

in front and hangs in long, fine pleats (sometimes cascaded

folds) under the arms, the ends of which reach below knees.

The material is not cut to form sleeves; instead two oblong

pieces of material are held together by small fastenings at

short intervals, showing upper arm through intervening

spaces. The result in appearance is similar to a kimono

sleeve. (Metropolitan Museum.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art Woman in Greek

Art about 400 B.C.

Metropolitan Museum of Art Woman in Greek

Art about 400 B.C.

That was some years back. We are a match for England to-day, in the

open, but have a long way to go before we wear with equal conviction,

and therefore easy grace, tea-gown and evening dress. Both how and

when still annoy us as a nation. On the street we are supreme when

tailleur. In carriage attire the French woman is supreme, by reason of

that innate Latin coquetry which makes her feel line and its

significance. The ideal pose for any hat is a French secret.

The average woman is partially aware that if she would be a decorative

being, she must grasp conclusively two points: first, the limitations of

her natural outline; secondly, a knowledge of how nearly she can

approach the outline demanded by fashion without appearing a

caricature, which is another way of saying that each woman should learn

to recognise her own type. The discussion of silhouette has become a

popular theme. In fact it would be difficult to find a maker of women's

costumes so remote and unread as not to have seized and imbedded deep in

her vocabulary that mystic word.

To make our points clear, constant reference to the stage is necessary;

for from stage effects we are one and all free to enjoy and learn.

Nowhere else can the woman see so clearly presented the value of having

what she wears harmonise with the room she wears it in, and the occasion

for which it is worn.

Not all plays depicting contemporary life are plays of social life,

staged and costumed in a chic manner. What is taught by the modern

stage, as shown by Bakst, Reinhardt, Barker, Urban, Jones, the

Portmanteau Theatre and Washington Square Players, is values, as the

artist uses the term—not fashions; the relative importance of

background, outline, colour, texture of material and how to produce

harmonious effects by the judicious combination of furnishings and

costumes.

To-day, when we want to say that a costume or the interior decoration of

a house is the last word in modern line and colour, we are apt to call

it à la Bakst, meaning of course Leon Bakst, whose American "poster" was

the Russian Ballet. If you have not done so already, buy or borrow the

wonderful Bakst book, showing reproductions in their colours of his

extraordinary drawings, the originals of which are owned by private

individuals or museums, in Paris, Petrograd, London, and New York. They

are outré to a degree, yet each one suggests the whole or parts of

costumes for modern woman—adorable lines, unbelievable combinations of

colour! No wonder Poiret, the Paris dressmaker, seized upon Bakst as

designer (or was it Bakst who seized upon Poiret?).

Bakst got his inspiration in the Orient. As a bit of proof, for your own

satisfaction, there is a book entitled Six Monuments of Chinese

Sculpture, by Edward Chauvannes, published in 1914, by G. Van Oest &

Cie., of Brussels and Paris. The author, with a highly commendable

desire to perpetuate for students a record of the most ancient

speciments of Chinese sculpture, brought to Paris and sold there, from

time to time, to art-collectors, from all over the world; selected six

fine speciments as theme of text and for illustrations.

Plate 23 in this collection shows a woman whose costume in outline

might have been taken from Bakst or even Vogue. But put it the other way

round: the Vogue artist to-day—we use the word as a generic term—finds

inspiration through museums and such works as the above. This is

particularly true as our little handbook goes into print, for the reason

that the great war between the Central Powers and the Entente has to a

certain extent checked the invention and material output of Europe, and

driven designers of and dealers in costumes for women, to China and

Japan.

Our great-great-grandmothers here in America wore Paris fashions shown

on the imported fashion dolls and made up in brocades from China, by the

Colonial mantua makers. So we are but repeating history.

To-day, war, which means horror, ugliness, loss of ideals and illusions,

holds most of the world in its grasp, and we find creative

artists—apostles of the Beautiful, seeking the Orient because it is

remote from the great world struggle. We hear that Edmund Dulac (who has

shown in a superlative manner, woman decorative, when illustrating the

Arabian Nights and other well-known books), is planning a flight to

the Orient. He says that he longs to bury himself far from carnage, in

the hope of wooing back his muse.

If this subject of background, line and colour, in relation to costuming

of woman, interests you, there are many ways of getting valuable points.

One of them, as we have said, is to walk through galleries looking at

pictures only as decorations; that is, colour and line against the

painter's background.

Fashions change, in dress, arrangement of hair, jewels, etc., but this

does not affect values. It is la ligne, the grand gesture, or line

fraught with meaning and balance and harmony of colour.

The reader knows the colour scheme of her own rooms and the character of

gowns she is planning, and for suggestions as to interesting colour

against colour, she can have no higher authority than the experience of

recognised painters. Some develop rapidly in this study of values.

If your rooms are so-called period rooms, you need not of necessity

dress in period costumes, but what is extremely important, if you would

not spoil your period room, nor fail to be a decorative contribution

when in it, is that you make a point of having the colour and texture of

your house gowns in the same key as the hangings and upholstery of your

room. White is safe in any room, black is at times too strong. It

depends in part upon the size of your room. If it is small and in soft

tones, delicate harmonising shades will not obtrude themselves as black

can and so reduce the effect of space. This is the case not only with

black, but with emerald green, decided shades of red, royal blue, and

purple or deep yellows. If artistic creations, these colours are all

decorative in a room done in light tones, provided the room is large.

A Louis XVI salon is far more beautiful if the costumes are kept in

Louis XVI colouring and all details, such as lace, jewelry, fans, etc.,

kept strictly within the picture; fine in design, delicate in colouring,

workmanship and quality of material. Beyond these points one may follow

the outline demanded by the fashion of the moment, if desired. But

remember that a beautiful, interesting room, furnished with works of

art, demands a beautiful, interesting costume, if the woman in question

would sustain the impression made by her rooms, to the arranging of

which she has given thought, time and vitality, to say nothing of

financial outlay; she must take her own decorative appearance seriously.

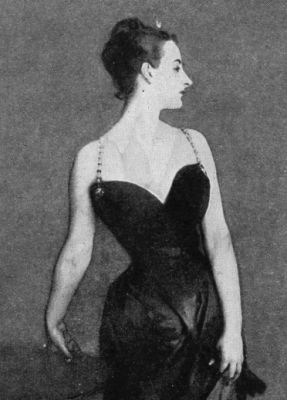

PLATE V

Example of the pointed head-dress, carefully concealed hair

(in certain countries at certain periods of history, a sign

of modesty), round necklace and very long close sleeves

characteristic of fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

Observe angle at which head-dress is worn.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Woman in Gothic Art

Portrait showing pointed head-dress

The writer has passed wonderful hours examining rare illuminated

manuscripts of the Middle Ages (twelfth, thirteenth, fourteenth and

fifteenth centuries), missals, "Hours" of the Virgin, and Breviaries,

for the sole purpose of studying woman's costumes,—their colour, line

and details, as depicted by the old artists. Gothic costumes in Gothic

interiors, and Early Renaissance costumes in Renaissance interiors.

The art of moderns in various media, has taken from these creations of

mediæval genius, more than is generally realized. We were looking at a

rare illuminated Gothic manuscript recently, from which William Morris

drew inspirations and ideas for the books he made. It is a monumental

achievement of the twelfth century, a mass book, written and illuminated

in Flanders; at one time in the possession of a Cistercian monastery,

but now one of the treasures in the noted private collection made by the

late J. Pierpont Morgan. The pages are of vellum and the illuminations

show the figures of saints in jewel-like colours on backgrounds of pure

gold leaf. The binding of this book,—sides of wood, held together by

heavy white vellum, hand-tooled with clasps of thin silver, is the work

of Morris himself and very characteristic of his manner. He patterned

his hand-made books after these great models, just as he worked years to

duplicate some wonderful old piece of furniture, realising so well the

magic which lies in consecrated labour, that labour which takes no

account of time, nor pay, but is led on by the vision of perfection

possessing the artist's soul.

We know women who have copied the line, colour and material of costumes

depicted in Gothic illuminations that they might be in harmony with

their own Gothic rooms. One woman familiar with this art, has planned a

frankly modern room, covering her walls with gold Japanese fibre,

gilding her woodwork and doors, using the brilliant blues, purples and

greens of the old illuminations in her hangings, upholstery and

cushions, and as a striking contribution to the decorative scheme,

costumes herself in white, some soft, clinging material such as crêpe de

chine, liberty satin or chiffon velvet, which take the mediæval lines,

in long folds. She wears a silver girdle formed of the hand-made clasps

of old religious books, and her rings, neck chains and earrings are all

of hand-wrought silver, with precious stones cut in the ancient way and

irregularly set. This woman got her idea of the effectiveness of white

against gold from an ancient missal in a famous private collection,

which shows the saints all clad in marvellous white against gold leaf.

Whistler's house at 2 Cheyne Road, London, had a room the dado and doors

of which were done in gold, on which he and two of his pupils painted

the scattered petals of white and pink chrysanthemums. Possibly a

Persian or Japanese effect, as Whistler leaned that way, but one sees

the same idea in an illumination of the early sixteenth century; "Hours"

of the Virgin and Breviary, made for Eleanor of Portugal, Queen of John

II. The decorations here are in the style of the Renaissance, not

Gothic, and some think Memling had a hand in the work. The borders of

the illumination, characteristic of the Bruges School, are gold leaf on

which is painted, in the most realistic way, an immense variety of

single flowers, small roses, pansies, violets, daisies, etc., and among

them butterflies and insects. This border surrounds the pictures which

illustrate the text. Always the marvellous colour, the astounding skill

in laying it on to the vellum pages, an unforgettable lesson in the

possibility of colour applied effectively to costumes, when background

is kept in mind. This Breviary was bound in green velvet and clasped

with hand-wrought silver, for Cardinal Rodrigue de Castro (1520-1600) of

Spain. It is now in the private collection of Mr. Morgan. The cover

alone gives one great emotion, genuine ancient velvet of the sixteenth

century, to imitate which taxes the ingenuity of the most skilful of

modern manufacturers.

CHAPTER III

HOW TO DRESS YOUR TYPE

A Few Points Applying to All Costumes

EEDLESS

to say, when considering woman's costumes, for ordinary use, in

their relation to background, unless some chameleon-like material be

invented to take on the colour of any background, one must be content

with the consideration of one's own rooms, porches, garden, opera-box or

automobile, etc. For a gown to be worn when away from home, when

lunching, at receptions or dinners, the first consideration must be

becomingness,—a careful selection of line and colour that bring out

the individuality of the wearer. When away from one's own setting,

personality is one of the chief assets of every woman. Remember,

individuality is nature's gift to each human being. Some are more

markedly different than others, but we have all seen a so-called

colourless woman transformed into surprising loveliness when dressed by

an artist's instinct. A delicate type of blond, with fair hair, quiet

eyes and faint shell-pink complexion, can be snuffed out by too strong

colours. Remember that your ethereal blond is invariably at her best in

white, black (never white and black in combination unless black with

soft white collars and frills) and delicate pastel shades.

EEDLESS

to say, when considering woman's costumes, for ordinary use, in

their relation to background, unless some chameleon-like material be

invented to take on the colour of any background, one must be content

with the consideration of one's own rooms, porches, garden, opera-box or

automobile, etc. For a gown to be worn when away from home, when

lunching, at receptions or dinners, the first consideration must be

becomingness,—a careful selection of line and colour that bring out

the individuality of the wearer. When away from one's own setting,

personality is one of the chief assets of every woman. Remember,

individuality is nature's gift to each human being. Some are more

markedly different than others, but we have all seen a so-called

colourless woman transformed into surprising loveliness when dressed by

an artist's instinct. A delicate type of blond, with fair hair, quiet

eyes and faint shell-pink complexion, can be snuffed out by too strong

colours. Remember that your ethereal blond is invariably at her best in

white, black (never white and black in combination unless black with

soft white collars and frills) and delicate pastel shades.

PLATE VI

Fifteenth-century costume. "Virgin and Child" in painted

terra-cotta.

It is by Andrea Verrocchio, and now in Metropolitan Museum.

We have here an illustration of the costume, so often shown

on the person of the Virgin in the art of the Middle Ages.

Metropolitan Museum of Art Woman in Art of

the Renaissance Sculpture-Relief in Terra-Cotta: The

Virgin

Metropolitan Museum of Art Woman in Art of

the Renaissance Sculpture-Relief in Terra-Cotta: The

Virgin

The richly-toned brunette comes into her own in reds, yellows and

low-tones of strong blue.

Colourless jewels should adorn your perfect blond, colourful gems your

glowing brunette.

What of those betwixt and between? In such cases let complexion and

colour of eyes act as guide in the choice of colours.

One is familiar with various trite rules such as match the eyes, carry

out the general scheme of your colouring, by which is meant, if you are

a yellow blond, go in for yellows, if your hair is ash-brown, your eyes

but a shade deeper, and your skin inclined to be lifeless in tone, wear

beaver browns and content yourself with making a record in harmony,

with no contrasting note.

Just here let us say that the woman in question must at the very outset

decide whether she would look pretty or chic, sacrificing the one for

the other, or if she insists upon both, carefully arrange a compromise.

As for example, combine a semi-picture hat with a semi-tailored dress.

The strictly chic woman of our day goes in for appropriateness; the

lines of the latest fashion, but adapted to bring out her own best

points, while concealing her bad ones, and an insistance upon a colour

and a shade of colour, sufficiently definite to impress the beholder at

a glance. This type of woman as a rule keeps to a few colours, possibly

one or two and their varieties, and prefers gowns of one material rather

than combinations of materials. Though she possess both style and

beauty, she elects to emphasise style.

In the case of the other woman, who would star her face at the expense

of her tout ensemble, colour is her first consideration,

multiplication of detail and intelligent expressing of herself in her

mise-en-scène. Seduisant, instead of chic is the word for this

woman.

Your black-haired woman with white skin and dark, brilliant eyes, is the

one who can best wear emerald green and other strong colours. The now

fashionable mustard, sage green, and bright magentas are also the

affaire of this woman with clear skin, brilliant colour and sparkling

eyes.

These same colours, if subdued, are lovely on the middle-aged woman with

black hair, quiet eyes and pale complexion, but if her hair is grey or

white, mustard and sage green are not for her, and the magenta must be

the deep purplish sort, which combines with her violets and mauves, or

delicate pinks and faded blues. She will be at her best in shades of

grey which tone with her hair.

CHAPTER IV

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF CLOTHES

AS

the reader ever observed the effect of clothes upon manners? It is

amazing, and only proves how pathetically childlike human nature is.

AS

the reader ever observed the effect of clothes upon manners? It is

amazing, and only proves how pathetically childlike human nature is.

Put any woman into a Marie Antoinette costume and see how, during an

evening she will gradually take on the mannerisms of that time. This

very point was brought up recently in conversation with an artist, who

in referring to one of the most successful costume balls ever given in

New York—the crinoline ball at the old Astor House—spoke of how our

unromantic Wall Street men fell to the spell of stocks, ruffled shirts

and knickerbockers, and as the evening advanced, were quite themselves

in the minuette and polka, bowing low in solemn rigidity, leading their

lady with high arched arm, grasping her pinched-in waist, and swinging

her beruffled, crinolined form in quite the 1860 manner.

Some women, even girls of tender years, have a natural instinct for

costuming themselves, so that they contribute in a decorative way to any

setting which chance makes theirs. Watch children "dressing up" and see

how among a large number, perhaps not more than one of them will have

this gift for effects. It will be she who knows at a glance which of the

available odds and ends she wants for herself, and with a sure, swift

hand will wrap a bright shawl about her, tie a flaming bit of silk about

her dark head, and with an assumed manner, born of her garb, cast a

magic spell over the small band which she leads on, to that which,

without her intense conviction and their susceptibility to her mental

attitude toward the masquerade, could never be done.

This illustrates the point we would make as to the effect of clothes

upon psychology. The actor's costume affects the real actor's psychology

as much or more than it does that of his audience. He is the man he

has made himself appear. The writer had the experience of seeing a

well-known opera singer, when a victim to a bad case of the grippe,

leave her hotel voiceless, facing a matinee of Juliet. Arrived in her

dressing-room at the opera, she proceeded to change into the costume for

the first act. Under the spell of her rôle, that prima donna seemed

literally to shed her malady with her ordinary garments, and to take on

health and vitality with her Juliet robes. Even in the Waltz song her

voice did not betray her, and apparently no critic detected that she was

indisposed.

In speaking of periods in furniture, we said that their story was one of

waves of types which repeated themselves, reflecting the ages in which

they prevailed. With clothes we find it is the same thing: the scarlet,

and silver and gold of the early Jacobeans, is followed by the drabs and

greys of the Commonwealth; the marvellous colour of the Church, where

Beauty was enthroned, was stamped out by the iron will of Cromwell who,

in setting up his standard of revolt, wrapped soul and body of the new

Faith in penal shades.

New England was conceived in this spirit and as mind had affected the

colour of the Puritans' clothes, so in turn the drab clothes, prescribed

by their new creed, helped to remove colour from the New England mind

and nature.

PLATE VII

Fifteenth-century costumes on the Holy Women at the Tomb of

our Lord.

The sculpture relief is enamelled terra-cotta in white,

blue, green, yellow and manganese colours. It bears the date

1487.

Note character of head-dresses, arrangement of hair, capes

and gowns which are Early Renaissance. (Metropolitan

Museum.)

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Woman in Art of the Renaissance

Sculpture-Relief in Terra-Cotta: Holy Women

But observe how, as prosperity follows privation, the mind expands,

reaching out for what the changed psychology demands. It is the old

story of Rome grown rich and gay in mood and dress. There were of

course, villains in Puritan drab and Grecian white, but the child in

every man takes symbol for fact. So it is that to-day, some shudder with

the belief that Beauty, re-enthroned in all her gorgeous modern hues,

means near disaster. The progressives claim that into the world has come

a new hope; that beneath our lovely clothes of rainbow tints, and within

our homes where Beauty surely reigns, a new psychology is born to

radiate colour from within.

Our advice to the woman not born with clothes sense, is: employ experts

until you acquire a mental picture of your possibilities and

limitations, or buy as you can afford to, good French models, under

expert supervision. You may never turn out to be an artist in the

treatment of your appearance, instinctively knowing how a prevailing

fashion in line and colour may be adapted to you, but you can be taught

what your own type is, what your strong points are, your weak ones, and

how, while accentuating the former, you may obliterate the latter.

There are two types of women familiar to all of us: the one gains in

vital charm and abandon of spirit from the consciousness that she is

faultlessly gowned; the other succumbs to self-consciousness and is

pitifully unable to extricate her mood from her material trappings.

For the darling of the gods who walks through life on clouds, head up

and spirit-free, who knows she is perfectly turned out and lets it go at

that, we have only grateful applause. She it is who carries every

occasion she graces—indoors, out-of-doors, at home, abroad. May her

kind be multiplied!

But to the other type, she who droops under her silks and gold tissue,

whose pearls are chains indeed, we would throw out a lifeline. Submerged

by clothes, the more she struggles to rise above them the more her

spirit flags. The case is this: the woman's mind is wrong; her clothes

are right—lovely as ever seen; her jewels gems; her house and car and

dog the best. It is her mind that is wrong; it is turned in,

instead of out.

Now this intense and soul-, as well as line-destroying

self-consciousness, may be prenatal, and it may result from the Puritan

attitude toward beauty; that old New England point of view that the

beautiful and the vicious are akin. Every young child needs to have

cultivated a certain degree of self-reliance. To know that one's

appearance is pleasing, to put it mildly, is of inestimable value when

it comes to meeting the world. Every child, if normal, has its good

points—hair, eyes, teeth, complexion or figure; and we all know that

many a stage beauty has been built up on even two of these attributes.

Star your good points, clothes will help you. Be a winner in your own

setting, but avoid the fatal error of damning your clothes by the spirit

within you.

The writer has in mind a woman of distinguished appearance, beauty,

great wealth, few cares, wonderful clothes and jewels, palatial homes;

and yet an envious unrest poisons her soul. She would look differently,

be different and has not the wisdom to shake off her fetters. Her

perfect dressing helps this woman; you would not be conscious of her

otherwise, but with her natural equipment, granted that she concentrated

upon flashing her spirit instead of her wealth, she would be a leader in

a fine sense. The Beauty Doctor can do much, but show us one who can put

a gleam in the eye, tighten the grasp, teach one that ineffable grace

which enables woman, young or old, to wear her clothes as if an integral

part of herself. This quality belongs to the woman who knows, though she

may not have thought it out, that clothes can make one a success, but

not a success in the enduring sense. Dress is a tyrant if you take it as

your god, but on the other hand dress becomes a magician's wand when

dominated by a clever brain. Gown yourself as beautifully as you can

afford, but with judgment. What we do, and how we do it, is often

seriously and strangely affected by what we have on. The writer has in

mind a literary woman who says she can never talk business except in a

linen collar! Mark Twain, in his last days, insisted that he wrote more

easily in his night-shirt. Richard Wagner deliberately put on certain

rich materials in colours and hung his room with them when composing

the music of The Ring. Chopin says in a letter to a friend: "After

working at the piano all day, I find that nothing rests me so much as to

get into the evening dress which I wear on formal occasions." In

monarchies based on militarism, royal princes, as soon as they can walk,

are put into military uniforms. It cultivates in them the desired

military spirit. We all associate certain duties with certain costumes,

and the extraordinary response to colour is familiar to all. We talk

about feeling colour and say that we can or cannot live in green, blue,

violet or red. It is well to follow this colour instinct in clothes as

well as in furnishing. You will find you are at your best in the colours

and lines most sympathetic to you.