The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Brighton Road, by Charles G. Harper

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Brighton Road

The Classic Highway to the South

Author: Charles G. Harper

Release Date: January 22, 2012 [EBook #38611]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BRIGHTON ROAD ***

Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive/American

Libraries.)

HISTORIES OF THE ROADS

—BY—

Charles G. Harper.

THE BRIGHTON ROAD: The Classic Highway to the South.

THE GREAT NORTH ROAD: London to York.

THE GREAT NORTH ROAD: York to Edinburgh.

THE DOVER ROAD: Annals of an Ancient Turnpike.

THE BATH ROAD: History, Fashion and Frivolity on an old Highway.

THE MANCHESTER AND GLASGOW ROAD: London to Manchester.

THE MANCHESTER ROAD: Manchester to Glasgow.

THE HOLYHEAD ROAD: London to Birmingham.

THE HOLYHEAD ROAD: Birmingham to Holyhead.

THE HASTINGS ROAD: And The “Happy Springs of Tunbridge.”

THE OXFORD, GLOUCESTER AND MILFORD HAVEN ROAD: London to Gloucester.

THE OXFORD, GLOUCESTER AND MILFORD HAVEN ROAD: Gloucester to Milford Haven.

THE NORWICH ROAD: An East Anglian Highway.

THE NEWMARKET, BURY, THETFORD AND CROMER ROAD.

THE EXETER ROAD: The West of England Highway.

THE PORTSMOUTH ROAD.

THE CAMBRIDGE, KING’S LYNX AND ELY ROAD.

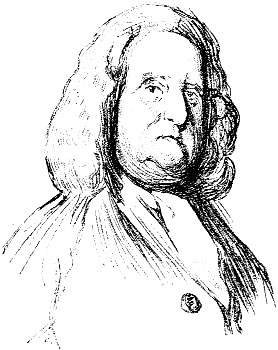

GEORGE THE FOURTH.

From the painting by Sir Thomas Lawrence, R.A.

The

BRIGHTON ROAD

The Classic Highway to the South

By CHARLES G. HARPER

Illustrated by the Author, and from old-time

Prints and Pictures

London:

CECIL PALMER

Oakley House, Bloomsbury Street, W.C. 1

First Published - 1892

Second Edition - 1906

Third and Revised Edition - 1922

Printed in Great Britain by C. Tinling & Co., Ltd.,

53, Victoria Street, Liverpool,

and 187, Fleet Street, London.

Many years ago it occurred to this writer that it would be an interesting thing to write and illustrate a book on the Road to Brighton. The genesis of that thought has been forgotten, but the book was written and published, and has long been out of print. And there might have been the end of it, but that (from no preconceived plan) there has since been added a long series of books on others of our great highways, rendering imperative re-issues of the parent volume.

Two considerations have made that undertaking a matter of considerable difficulty, either of them sufficiently weighty. The first was that the original book was written at a time when the author had not arrived at a settled method; the second is found in the fact of the Brighton Road being not only the best known of highways, but also the one most susceptible to change.

When it is remembered that motor-cars have come upon the roads since then, that innumerable sporting “records” in cycling, walking, and other forms of progression have since been made, and that in many other ways the road is different, it was seen that not merely a re-issue of the book, but a book almost entirely re-written and re-illustrated was required. This, then, is what was provided in a second edition, published in 1906. And now another, the third, is issued, bringing the story of this highway up to date.

CHARLES G. HARPER.

March, 1922.

| MILES | |

| Westminster Bridge (Surrey side) to— | |

| St. Mark’s Church, Kennington | 1½ |

| Brixton Church | 3 |

| Streatham | 5½ |

| Norbury | 6¾ |

| Thornton Heath | 8 |

| Croydon (Whitgift’s Hospital) | 9½ |

| Purley Corner | 12 |

| Smitham Bottom | 13½ |

| Coulsdon Railway Station | 14¼ |

| Merstham | 17¾ |

| Redhill (Market Hall) | 20½ |

| Horley (“Chequers”) | 24 |

| Povey Cross | 25¾ |

| Kimberham Bridge (Cross River Mole) | 26 |

| Lowfield Heath | 27 |

| Crawley | 29 |

| Pease Pottage | 31¼ |

| Hand Cross | 33½ |

| Staplefield Common | 34¾ |

| Slough Green | 36¼ |

| Whiteman’s Green | 37¼ |

| Cuckfield | 37½ |

| Ansty Cross | 38 |

| Bridge Farm (Cross River Adur) | 40¼ |

| St. John’s Common | 40¾ |

| “Friar’s Oak” Inn | 42¾ |

| Stonepound | 43½ |

| Clayton | 44½ |

| Pyecombe | 45½ |

| Patcham | 48 |

| Withdean | 48¾ |

| Preston | 49¾ |

| Brighton (Aquarium) | 51½ |

| The Sutton and Reigate Route | |

| St. Mark’s, Kennington | 1½ |

| Tooting Broadway | 6 |

| Mitcham | 8¼ |

| Sutton (“Greyhound”) | 11 |

| Tadworth | 16 |

| Lower Kingswood | 17 |

| Reigate Hill | 19¼ |

| Reigate (Town Hall) | 20½ |

| Woodhatch (“Old Angel”) | 21½ |

| Povey Cross | 26 |

| Brighton | 51⅝ |

| The Bolney and Hickstead Route | |

| Hand Cross | 33½ |

| Bolney | 39 |

| Hickstead | 40½ |

| Savers Common | 42 |

| Newtimber | 44½ |

| Pyecombe | 45 |

| Brighton | 50½ |

| PAGE | |

| George the Fourth | Frontispiece |

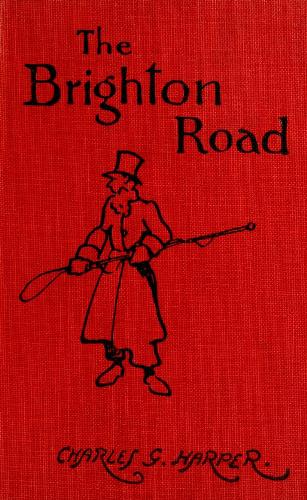

| Sketch-map showing Principal Routes to Brighton | 4 |

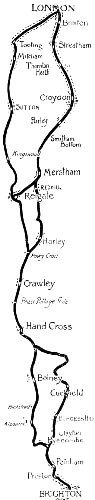

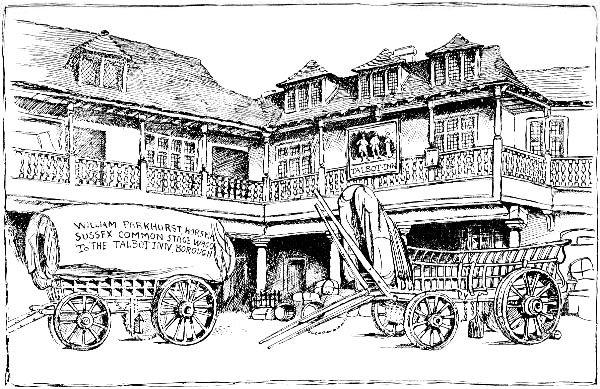

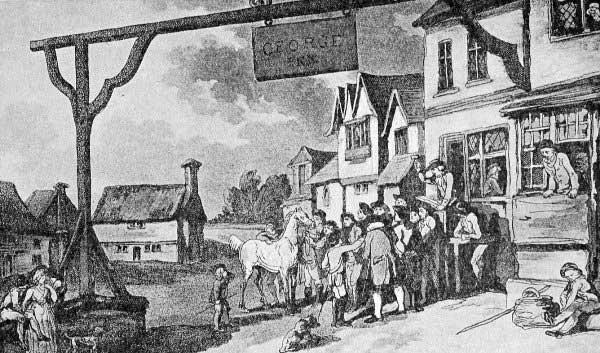

| Stage Waggon, 1808 | 13 |

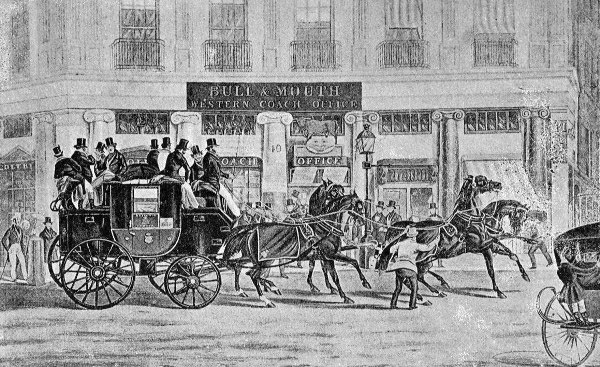

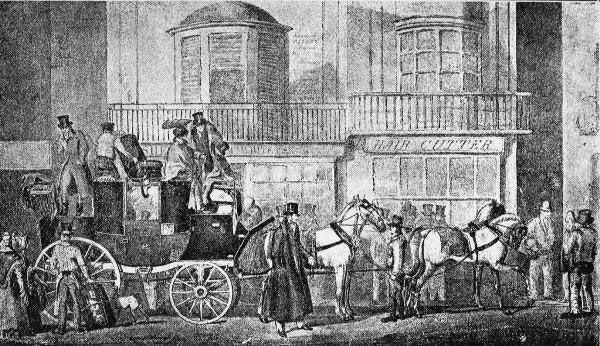

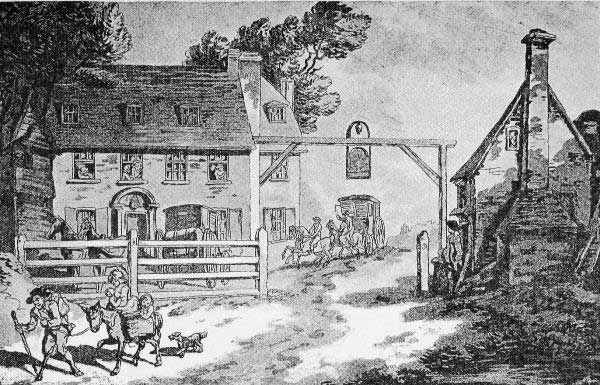

| The “Talbot” Inn Yard, Borough, about 1815 | 17 |

| Me and My Wife and Daughter | 19 |

| The “Duke of Beaufort” Coach starting from the “Bull and Mouth” Office, Piccadilly Circus, 1826 |

31 |

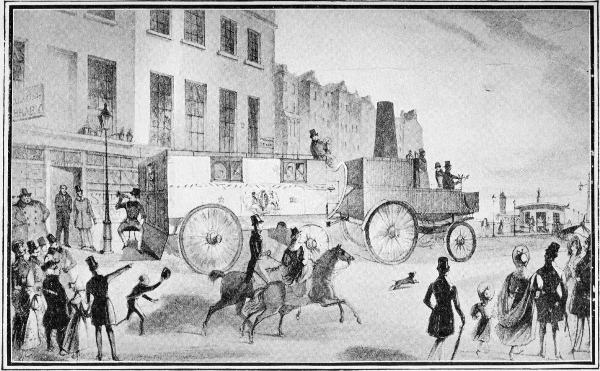

| The “Age,” 1829, starting from Castle Square, Brighton | 35 |

| Sir Charles Dance’s Steam-carriage leaving London for Brighton, 1833 | 39 |

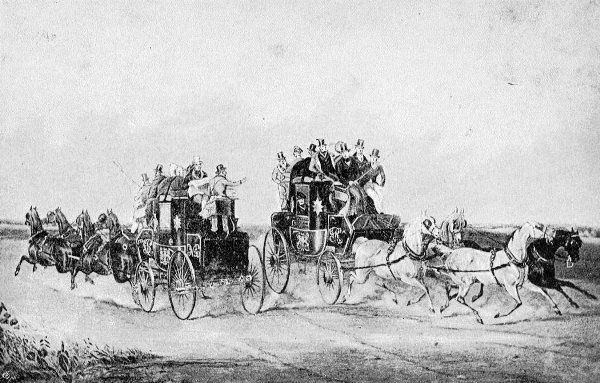

| The Brighton Day Mails crossing Hookwood Common, 1838 | 43 |

| The “Age,” 1852, crossing Ham Common | 47 |

| The “Old Times,” 1888 | 51 |

| The “Comet,” 1890 | 55 |

| John Mayall, Junior, 1869 | 70 |

| The Stock Exchange Walk: E. F. Broad at Horley | 83 |

| Miss M. Foster, paced by Motor Cycle, passing Coulsdon | 86 |

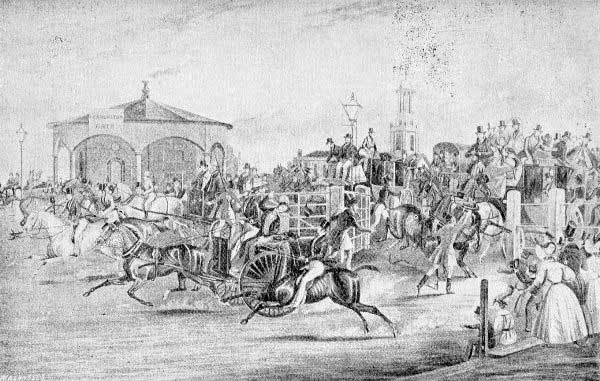

| Kennington Gate: Derby Day, 1839 | 95 |

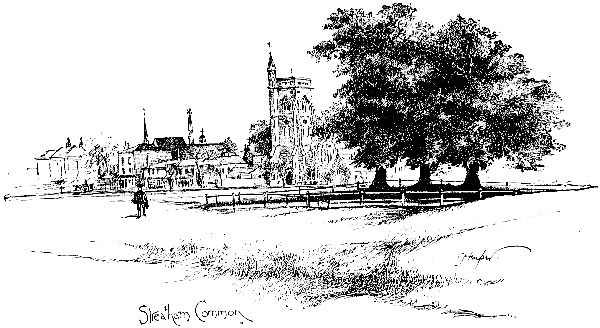

| Streatham Common | 101 |

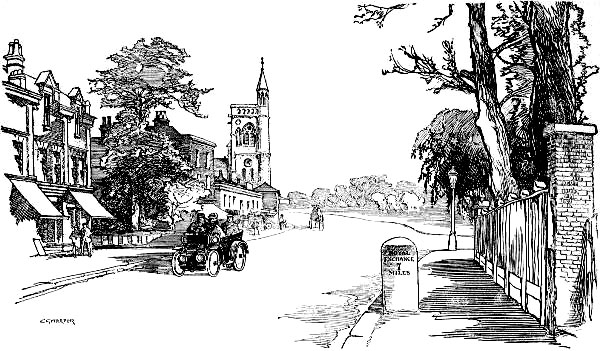

| Streatham | 107 |

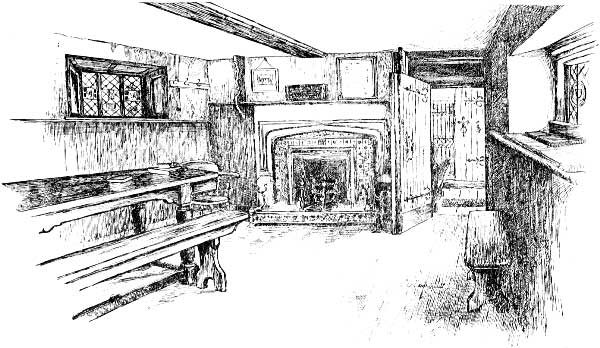

| The Dining Hall, Whitgift Hospital | 111 |

| The Chapel, Hospital of the Holy Trinity | 113 |

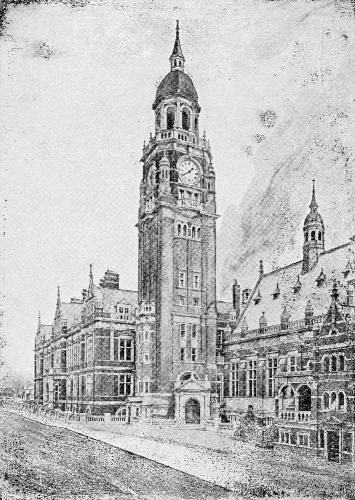

| Croydon Town Hall | 120 |

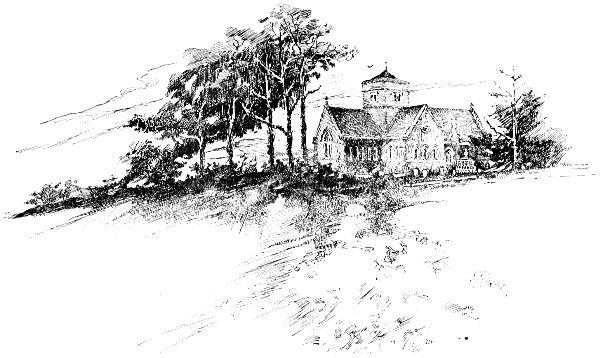

| Chipstead Church | 135 |

| Merstham | 139 |

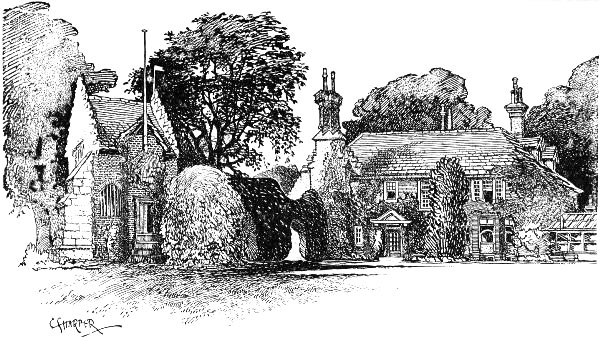

| Gatton Hall and “Town Hall” | 144 |

| The Switchback Road, Earlswood Common | 148 |

| Thunderfield Castle | 150 |

| The “Chequers,” Horley | 151 |

| The “Six Bells,” Horley | 153 |

| The “Cock,” Sutton, 1789 | 157 |

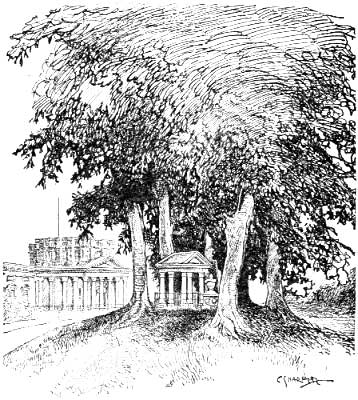

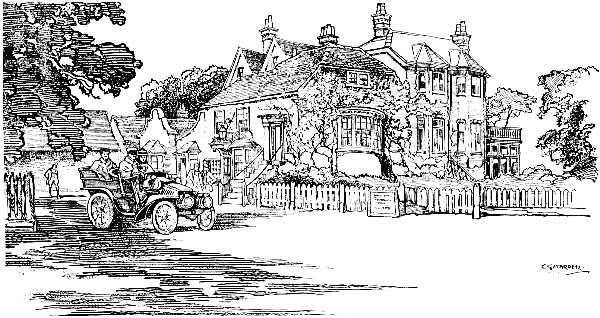

| Kingswood Warren | 162 |

| The Suspension Bridge, Reigate Hill | 163 |

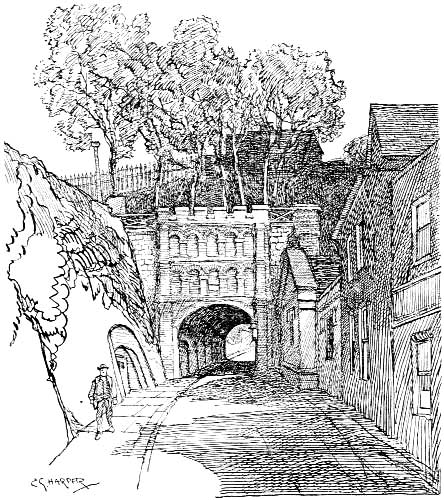

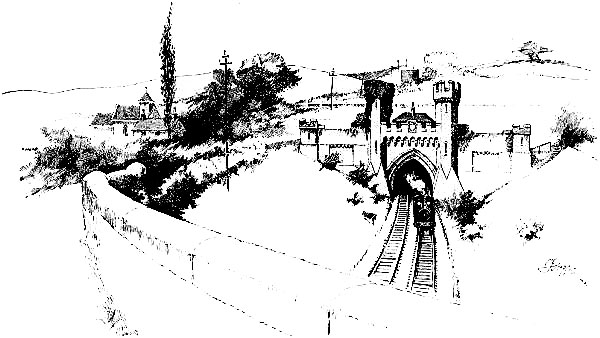

| The Tunnel, Reigate | 167 |

| Tablet, Batswing Cottages | 172 |

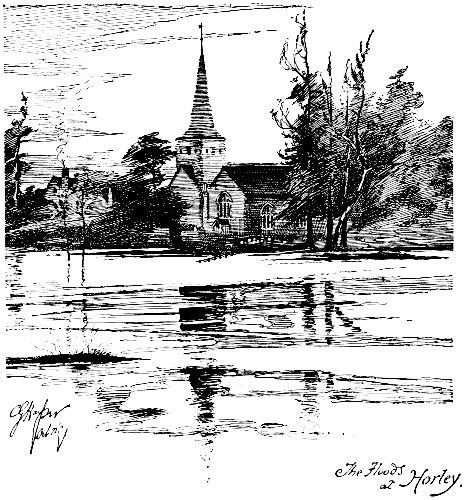

| The Floods at Horley | 174 |

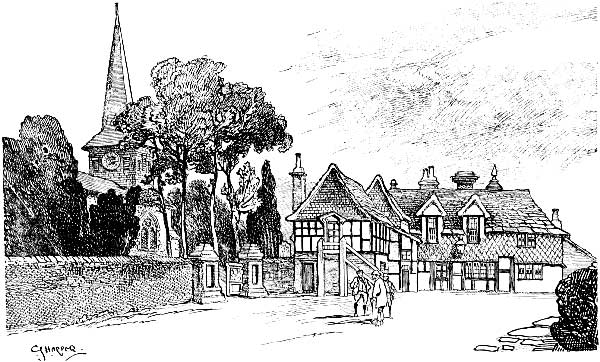

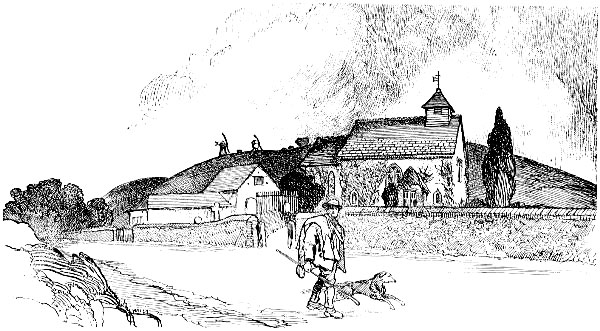

| Charlwood | 176 |

| A Corner in Newdigate Church | 177 |

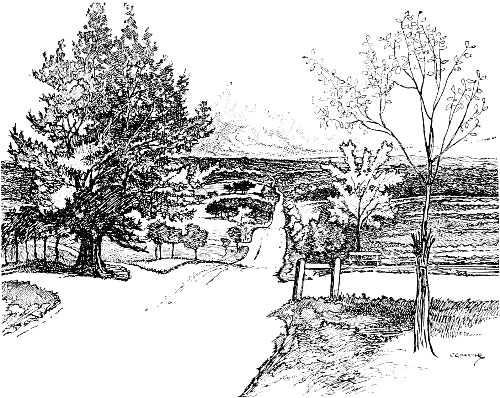

| On the Road to Newdigate | 179 |

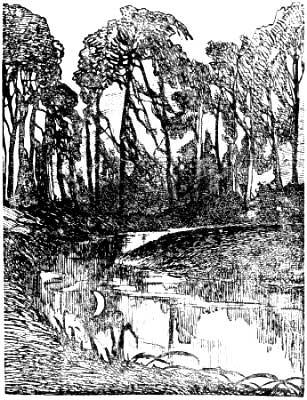

| Ifield Mill Pond | 180 |

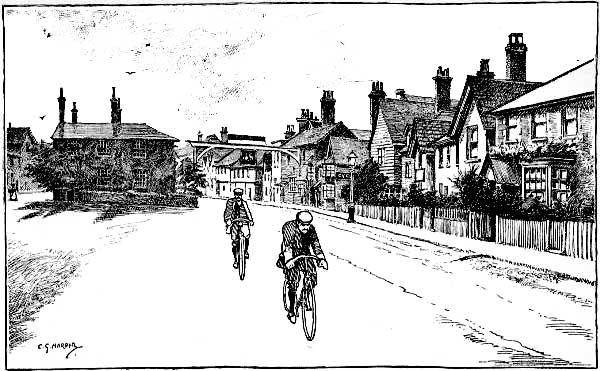

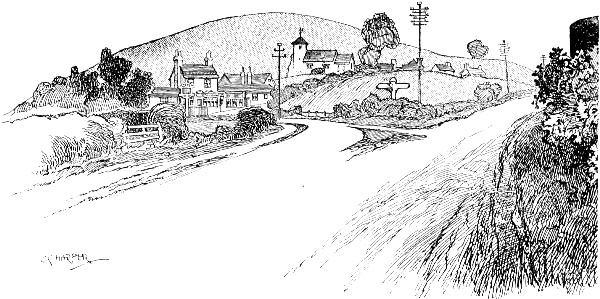

| Crawley: Looking South | 183 |

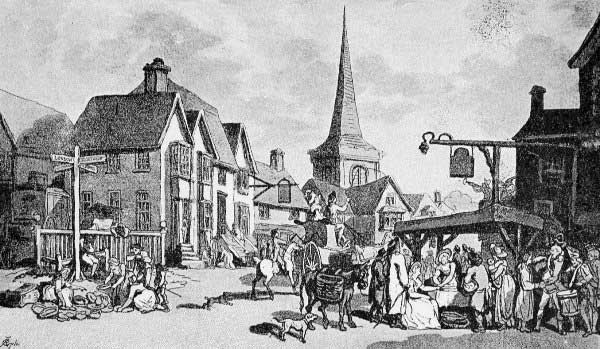

| Crawley, 1789 | 185 |

| An Old Cottage at Crawley | 188 |

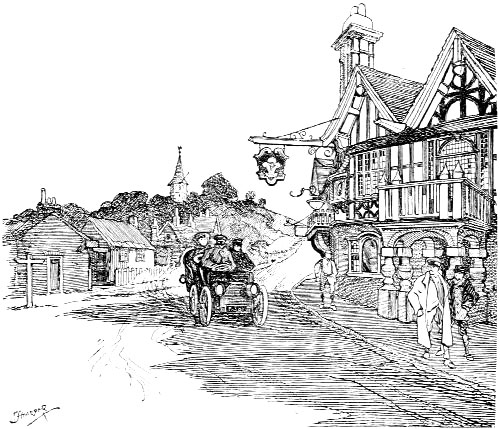

| The “George,” Crawley | 189 |

| Sculptured Emblem of the Holy Trinity, Crawley Church | 191 |

| Pease Pottage | 197 |

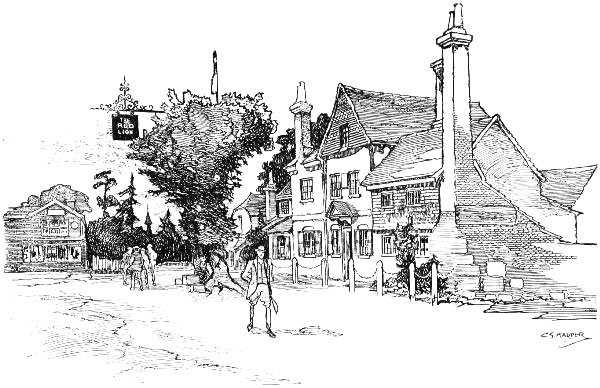

| The “Red Lion,” Hand Cross | 201 |

| Cuckfield, 1789 | 203 |

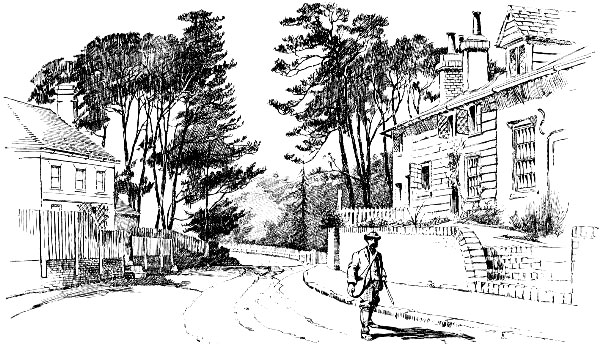

| The Road out of Cuckfield | 207 |

| Cuckfield Place | 210 |

| The Clock-Tower and Haunted Avenue, Cuckfield Place | 211 |

| Harrison Ainsworth | 213 |

| Old Sussex Fireback, Ridden’s Farm | 223 |

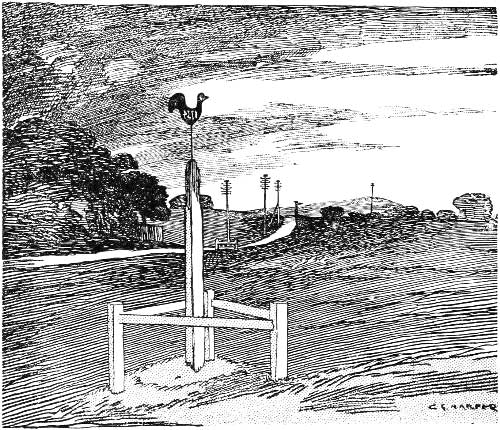

| Jacob’s Post | 224 |

| Clayton Tunnel | 233 |

| Clayton Church and the South Downs | 235 |

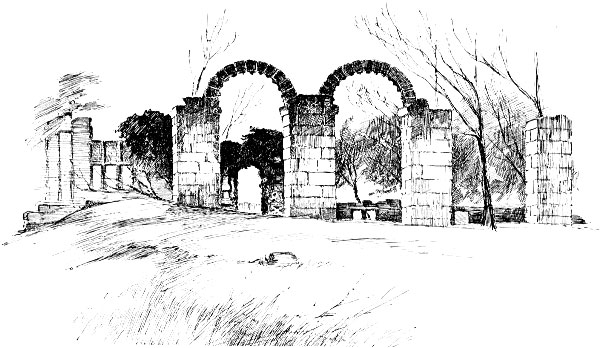

| The Ruins of Slaugham Place | 239 |

| The Entrance: Ruins of Slaugham Place | 241 |

| Bolney | 243 |

| From a Brass at Slaugham | 244 |

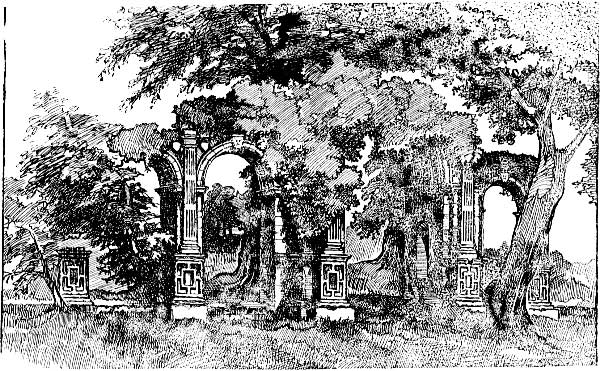

| Hickstead Place | 245 |

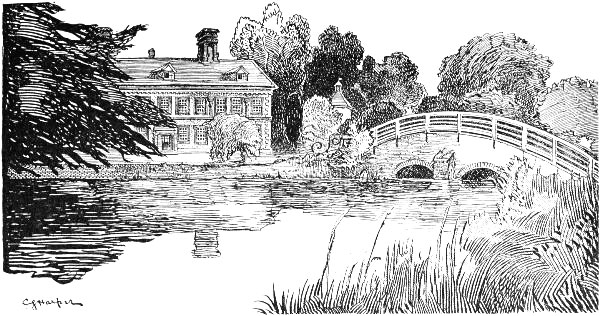

| Newtimber Place | 247 |

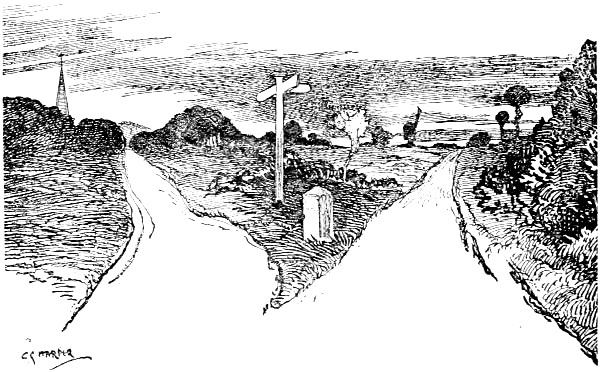

| Pyecombe: Junction of the Roads | 249 |

| Patcham | 251 |

| Old Dovecot, Patcham | 254 |

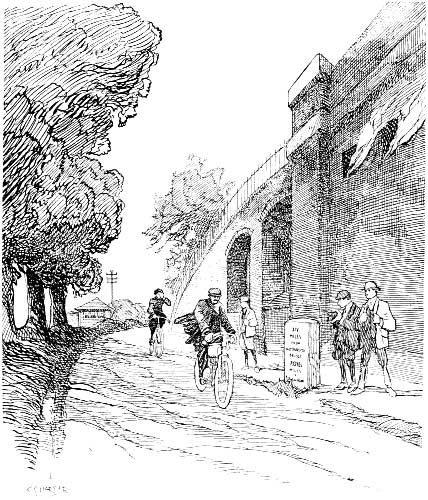

| Preston Viaduct: Entrance to Brighton | 256 |

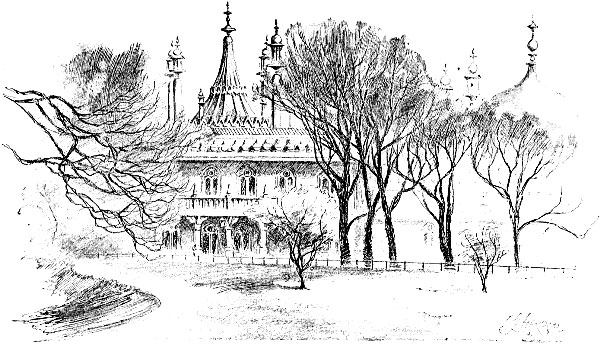

| The Pavilion | 259 |

| The Cliffs, Brighthelmstone, 1789 | 263 |

| Dr. Richard Russell | 265 |

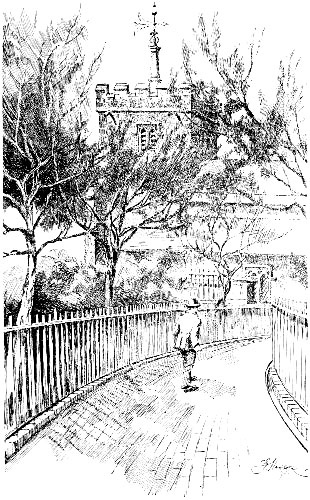

| St. Nicholas, the old Parish Church of Brighthelmstone | 269 |

| The Aquarium, before destruction of the Chain Pier | 271 |

The road to Brighton—the main route, pre-eminently the road—is measured from the south side of Westminster Bridge to the Aquarium. It goes by Croydon, Redhill, Horley, Crawley, and Cuckfield, and is (or is supposed to be) 51½ miles in length. Of this prime route—the classic way—there are several longer or shorter variations, of which the way through Clapham, Mitcham, Sutton, and Reigate, to Povey Cross is the chief. The modern “record” route is the first of these two, so far as Hand Cross, where it branches off and, instead of going through Cuckfield, proceeds to Brighton by way of Hickstead and Bolney, avoiding Clayton Hill and rejoining the initial route at Pyecombe.

The oldest road to Brighton is now but little used. It is not to be indicated in few words, but may be taken as the line of road from London Bridge, along the Kennington Road, to Brixton, Croydon, Godstone Green, Tilburstow Hill, Blindley Heath, East Grinstead, Maresfield, Uckfield, and Lewes; some fifty-nine miles. This is without doubt the most picturesque route. A circuitous way, travelled by some coaches was by[Pg 2] Ewell, Leatherhead, Dorking, Horsham, and Mockbridge (doubtless, bearing in mind the ancient mires of Sussex, originally “Muckbridge”), and was 57½ miles in length. An extension of this route lay from Horsham through Steyning, bringing up the total mileage to sixty-one miles three furlongs.

This multiplicity of ways meant that, in the variety of winding lanes which led to the Sussex coast, long before the fisher village of Brighthelmstone became that fashionable resort, Brighton, there were places on the way quite as important to the old waggoners and carriers as anything at the end of the journey. They set out the direction, and roads, when they began to be improved, were often merely the old routes widened, straightened, and metalled. They were kept very largely to the old lines, and it was not until quite late in the history of Brighton that the present “record” route in its entirety existed at all.

Among the many isolated roads made or improved, which did not in the beginning contemplate getting to Brighton at all, the pride of place certainly belongs to the ten miles between Reigate and Crawley, originally made as a causeway for horsemen, and guarded by posts, so that wheeled traffic could not pass. This was constructed under the Act 8th William III., 1696, and was the first new road made in Surrey since the time of the Romans.

It remained as a causeway until 1755, when it was widened and thrown open to all traffic, on paying toll. It was not only the first road to be made, but the last to maintain toll-gates on the way to Brighton, the Reigate Turnpike Trust expiring on the midnight of October 31st, 1881, from which time the Brighton Road became free throughout.

Meanwhile, the road from London to Croydon was repaired in 1718; and at the same time the road from London to Sutton was declared to be “dangerous to all persons, horses, and other cattle,” and almost impassable during five months of the year, and was therefore repaired, and toll-gates set up along it.

[Pg 3]Between 1730 and 1740 Westminster Bridge was building, and the roads in South London, including the Westminster Bridge Road and the Kennington Road, were being made. In 1755 the road (about ten miles) across the heaths and downs from Sutton to Reigate, was authorised, and in 1770 the Act was passed for widening and repairing the lanes from Povey Cross to County Oak and Brighthelmstone, by Cuckfield. By this time, it will be seen, Brighton had begun to be the goal of these improvements.

The New Chapel and Copthorne road, on the East Grinstead route, was constructed under the Act of 1770, the route across St. John’s Common and Burgess Hill remodelled in 1780, and the road from South Croydon to Smitham Bottom, Merstham, and Reigate was engineered out of the narrow lanes formerly existing on that line in 1807-8, being opened, “at present toll-free,” June 4th. 1808.

In 1813 the Bolney and Hickstead road, between Hand Cross and Pyecombe, was opened, and in 1816 the slip-road, avoiding Reigate, through Redhill, to Povey Cross. Finally, sixty yards were saved on the Reigate route by the cutting of the tunnel under Reigate Castle, in 1823. In this way the Brighton road, on its several branches, grew to be what it is now.

The Brighton Road, it has already been said, is measured from the south side of Westminster Bridge, which is the proper starting-point for record-makers and breakers; but it has as many beginnings as Homer had birthplaces. Modern coaches and motor-car services set out from the barrack-like hotels of Northumberland Avenue, or other central points, and the old carriers came to and went from the Borough High Street; but the Corinthian starting-point in the brave old days of the Regency and of George the Fourth was the “White Horse Cellar”—Hatchett’s “White Horse Cellar”—in Piccadilly. There, any day throughout the year, the knowing ones were gathered—with those green goslings who wished to be thought knowing—exchanging the latest scandal and[Pg 4] sporting gossip of the road, and rooking and being rooked; the high-coloured, full-blooded ancestors of the present generation, which looks upon them as a quite different order of beings, and can scarce believe in the reality of those full habits, those port-wine countenances, those florid garments that were characteristic of the age.

No one now starts from the “White Horse Cellar,” for the excellent reason that it does not now exist. The original “Cellar” was a queer place. Figure to yourself a basement room, with sanded floor, and an odour like that of a wine-vault, crowded with Regency bucks drinking or discussing huge beef-steaks.

It was situated on the south side of Piccadilly, where the Hotel Ritz now stands, and is first mentioned in 1720, when it was given its name by Williams, the landlord, in compliment to the House of Hanover, the newly-established Royal House of Great Britain, whose cognizance was a white horse. Abraham Hatchett first made the Cellar famous, both as a boozing-ken and a coach-office, and removed it to the opposite side of the street, where, as “Hatchett’s Hotel and White[Pg 5] Horse Cellar.” it remained until 1884, when the present “Albemarle” arose on its site, with a “White Horse” restaurant in the basement.

What Piccadilly and the neighbourhood of the “White Horse Cellar” were like in the times of Tom and Jerry, we may easily discover from the contemporary pages of “Real Life in London,” written by one “Bob Tallyho,” recounting the adventures of himself and “Tom Dashall.” A prize-fight was to be held on Copthorne Common between Jack Randall, “the Nonpareil”—called in the pronunciation of that time the “Nunparell”—and Martin, endeared to “the Fancy” as the “Master of the Rolls.”[1] Naturally, the roads were thronged, and “Piccadilly was all in motion—coaches, carts, gigs, tilburies, whiskies, buggies, dogcarts, sociables, dennets, curricles, and sulkies were passing in rapid succession, intermingled with tax-carts and waggons decorated with laurel, conveying company of the most varied description. Here was to be seen the dashing Corinthian tickling up his tits, and his bang-up set-out of blood and bone, giving the go-by to a heavy drag laden with eight brawny, bull-faced blades, smoking their way down behind a skeleton of a horse, to whom, in all probability, a good feed of corn would have been a luxury; pattering among themselves, occasionally chaffing the more elevated drivers by whom they were surrounded, and pushing forward their nags with all the ardour of a British merchant intent upon disposing of a valuable cargo of foreign goods on ’Change. There was a waggon full of all sorts upon the lark, succeeded by a donkey-cart with four insides: but Neddy, not liking his burthen, stopped short in the way of a dandy, whose horse’s head, coming plump up to the back of the crazy vehicle at the moment of its stoppage, threw the rider into the arms of a dustman, who, hugging his customer with the determined grasp of a bear, swore, d—n his eyes, he had saved his life, and he expected he would stand something handsome for the Gemmen all round,[Pg 6] for if he had not pitched into their cart he would certainly have broke his neck; which being complied with, though reluctantly, he regained his saddle, and proceeded a little more cautiously along the remainder of the road, while groups of pedestrians of all ranks and appearances lined each side.”

On their way they pass Hyde Park Corner, where they encounter one of a notorious trio of brothers, friends of the Prince Regent and companions of his in every sort of excess—the Barrymores, to wit, named severally Hellgate, Newgate, and Cripplegate, the last of this unholy trinity so called because of his chronic limping; the two others’ titles, taken with the characters of their bearers, are self-explanatory.

Dashall points his lordship out to his companion, who is new to London life, and requires such explanations.

“The driver of that tilbury,” says he, “is the celebrated Lord Cripplegate,[2] with his usual equipage; his blue cloak with a scarlet lining hanging loosely over the vehicle gives an air of importance to his appearance, and he is always attended by that boy, who has been denominated his Cupid: he is a nobleman by birth, a gentleman by courtesy (oh, witty Dashall!), and a gamester by profession. He exhausted a large estate upon odd and even, seven’s the main, etc., till, having lost sight of the main chance, he found it necessary to curtail his establishment and enliven his prospects by exchanging a first floor for a second, without an opportunity of ascertaining whether or not these alterations were best suited to his high notions or exalted taste; from which, in a short time, he was induced, either by inclination or necessity, to take a small lodging in an obscure street, and to sport a gig and one horse, instead of a curricle and pair, though in former times he used to drive four-in-hand, and was acknowledged to be an excellent whip. He still, however, possessed money enough to collect together a large quantity of halfpence, which in his hours of relaxation he managed to turn to good account by the[Pg 7] following stratagem:—He distributed his halfpence on the floor of his little parlour in straight lines, and ascertained how many it would require to cover it. Having thus prepared himself, he invited some wealthy spendthrifts (with whom he still had the power of associating) to sup with him, and he welcomed them to his habitation with much cordiality. The glass circulated freely, and each recounted his gaming or amorous adventures till a late hour, when, the effects of the bottle becoming visible, he proposed, as a momentary suggestion, to name how many halfpence, laid side by side, would carpet the floor, and offered to lay a large wager that he would guess the nearest.

“‘Done! done!’ was echoed round the room. Every one made a deposit of £100, and every one made a guess, equally certain of success; and his lordship declaring he had a large stock of halfpence by him, though perhaps not enough, the experiment was to be tried immediately. ’Twas an excellent hit!

“The room was cleared; to it they went; the halfpence were arranged rank and file in military order, when it appeared that his lordship had certainly guessed (as well he might) nearest to the number. The consequence was an immediate alteration of his lordship’s residence and appearance: he got one step in the world by it. He gave up his second-hand gig for one warranted new; and a change in his vehicle may pretty generally be considered as the barometer of his pocket.”

And so, with these piquant biographical remarks, they betook themselves along the road in the early morning, passing on their way many curious itinerants, whose trades have changed and decayed, and are now become nothing but a dim and misty memory; as, for instance, the sellers of warm “salop,” the forerunners of the early coffee-stalls of our own day.

But hats off to the Prince of Wales, the Prince Regent, the King! Never, while the Brighton Road remains the road to Brighton, shall it be dissociated from George the Fourth, who, as Prince, had a palace at either end, and made these fifty-odd miles in a very special sense a Via Regia. It was in 1782, when but twenty years of age, that he first knew Brighton, and until the last—for close upon forty-eight years—it retained his affections. He is thus the presiding genius of the way; and because, when we speak or think of the Brighton Road, we cannot help thinking of him, I have appropriately placed the portrait of George the Fourth, by the courtly Lawrence, in this book.

The Prince and King was the inevitable product of his times and of his upbringing: we mostly are. Only the rarest and most forceful figures can mould the world to their own form.

The character of George the Fourth has been the theme of writers upon history and sociology, of essayists, diarists, and gossip-mongers without number, and most of them have pictured him in very dark colours indeed. But Horace Walpole, perhaps the clearest-headed of this company, shows in his “Last Journals” that from his boyhood the Prince was governed in the stupidest way—in a manner, indeed, but too well fitted to spoil a spirit so high and so impetuous, and impulses so generous as then were his.

He proves what we may abundantly learn from other sources, that the narrow-minded and obstinate George the Third, petty and parochial in public and in private, was jealous of his son’s superior parts, and endeavoured to hide his light beneath the bushel of seclusion and inadequate training. It was impossible for such a father to appreciate either the qualities or the defects of such a son. “The uncommunicative selfishness and pride of George the Third confined him to domestic virtues,” says Walpole, and adds, “Nothing could equal the King’s attention to seclude his son[Pg 9] and protract his nonage. It went so absurdly far that he was made to wear a shirt with a frilled collar like that of babies. He one day took hold of his collar and said to a domestic, ‘See how I am treated!’”

The Duke of Montagu, too, was charged with the education of the Prince, and “he was utterly incapable of giving him any kind of instruction.... The Prince was so good-natured, but so uninformed, that he often said, ‘I wish anybody would tell me what I ought to do; nobody gives me any instruction for my conduct.’” The absolute poverty of the instruction afforded him, the false and narrow ways of the royal household, and the evil example and low companionship of his uncle, the Duke of Cumberland, did much to spoil the Prince.

To quote Walpole again: “It made men smile to find that in the palace of piety and pride his Royal Highness had learnt nothing but the dialect of footmen and grooms.... He drunk hard, swore, and passed every night in[3] ...; such were the fruits of his being locked up in the palace of piety.”

He proved, too, an intractable and undutiful son; but that was the result to be expected, and we cannot join Thackeray in his sentimental snivel over George the Third.

He was a faithless husband, but his wife was impossible, and even the mob who supported her quailed when the Marquis of Anglesey, baited in front of his house and compelled to drink her health, did so with the bitter rider, “And may all your wives be like her!”

All high-spirited young England flocked to the side of the Prince of Wales. He was the Grand Master of Corinthianism and Tom-and-Jerryism. It was he who peopled these roads with a numerous and brilliant concourse of whirling travellers, where before had been only infrequent plodders amidst the Sussex sloughs. To his princely presence, radiant by the Old Steyne, hasted all manner of people; prince and prizefighter,[Pg 10] statesman and nobleman; beauties noble and ignoble, and all who lived their lives. There he made incautious guests helplessly drunk on the potent old brandy he called “Diabolino,” and then exposed them in embarrassing situations; and there—let us remember it—he entertained, and was the beneficent patron of, the foremost artists and literary men of his age. The Zeitgeist (the Spirit of the Time) resided in, was personified in, and radiated from him. He was the First Gentleman in Europe, but is to us, in the perspective of a hundred years or so, something more: the type and exemplar of an age.

He should have been endowed with perennial youth, but even his splendid vitality faded at last, and he grew stout. Leigh Hunt called him a “fat Adonis of fifty,” and was flung into prison for it; and prison is a fitting place for a satirist who is stupid enough to see a misdemeanour in those misfortunes. No one who could help it would be fat, or fifty. Besides, to accuse one royal personage of being fat is to reflect upon all: it is an accompaniment of royalty.

Thackeray denounced his wig; but there is a prejudice in favour of flowing locks, and the King gracefully acknowledged it. One is not damned for being fat, fifty, and wearing a wig; and it seems a curious code of morality that would have it so; for although we may not all lose our hair nor grow fat, we must all, if we are not to die young, grow old and pass the grand climacteric.

There has been too much abuse of the Regency times. Where modern moralists, folded within their little sheep-walks from observation of the real world, mistake is in comparing those times with these, to the disadvantage of the past. They know nothing of life in the round, and seeing it only in the flat, cannot predicate what exists on the other side. To them there is, indeed, no other side, and things, despite the poet, are what they seem, and nothing else.

They lash the manners of the Regency, and think they are dealing out punishment to a bygone state of[Pg 11] things; but human nature is the same in all centuries. The fact is so obvious that one is ashamed to state it. The Regency was a terrible time for gambling; but Tranby Croft had a similar repute when Edward the Seventh was Prince of Wales. Bridge is a fine game, and what, think you, supports the evening newspapers? The news? Certainly: the Betting News. Cock-fighting was a brutal sport, and is now illegal, but is it dead? Oh dear, no. Virtue was not general in the picturesque times of George the Fourth. Is it now? Study the Cause Lists of the Divorce Courts. Worse offences are still punished by law, but are later condoned or explained by Society as an eccentricity. Society a hundred years ago did not plumb such depths.

In short, behind the surface of things, the Regency riot not only exists, but is outdone, and Tom and Jerry, could they return, would find themselves very dull dogs indeed. It is all the doing of the middle classes, that the veil is thrown over these things. In times when the middle class and the Nonconformist Conscience traditionally lived at Clapham, it mattered comparatively little what excesses were committed; but that class has so increased that it has to be subdivided into Upper and Lower, and has Claphams of its own everywhere. It is—or they are—more wealthy than before, and they read things, you know, and are a power in Parliament, and are something in the dominie sort to those other classes above and below.

The coaching and waggoning history of the road to Brighthelmstone (as it then was called) emerges dimly out of the formless ooze of tradition in 1681. In De Laune’s “Present State of Great Britain,” published in that year, in the course of a list of carriers, coaches, and stage-waggons in and out of London, we find[Pg 12] Thomas Blewman, carrier, coming from “Bredhempstone” to the “Queen’s Head,” Southwark, on Wednesdays, and, setting forth again on Thursdays, reaching Shoreham the same day: which was remarkably good travelling for a carrier’s waggon in the seventeenth century. Here, then, we have the Father Adam, the great original, so far as records can tell us, of all the after charioteers of the Brighton Road. It is not until 1732, that, from the pages of “New Remarks on London,” published by the Company of Parish Clerks, we hear anything further. At that date a coach set out on Thursdays from the “Talbot,” in the Borough High Street, and a van on Tuesdays from the “Talbot” and the “George.” In the summer of 1745 the “Flying Machine” left the “Old Ship,” Brighthelmstone at 5.30 a.m., and reached Southwark in the evening.

But the first extended and authoritative notice is found in 1746, when the widow of the Lewes carrier advertised in The Lewes Journal of December 8th that she was continuing the business:

Thomas Smith, the Old Lewes Carrier, being dead, THE BUSINESS IS NOW CONTINUED BY HIS WIDOW, MARY SMITH, who gets into the “George Inn,” in the Borough, Southwark, EVERY WEDNESDAY in the afternoon, and sets out for Lewes EVERY THURSDAY morning by eight o’clock, and brings Goods and Passengers to Lewes, Fletching, Chayley, Newick and all places adjacent at reasonable rates.

Performed (if God permit) by

MARY SMITH.

We may perceive by these early records that the real original way down to the Sussex coast was by the Croydon, Godstone, East Grinstead and Lewes route, and that its outlet must have been Newhaven, which, despite its name, is so very ancient a place, and was a port and harbour when Brighthelmstone was but a fisher-village.

STAGE WAGGON, 1808.

From a contemporary drawing.

That is the only glimpse we get of the widow Smith and her waggon; but the “George Inn, in the[Pg 14] Borough,” that she “got into,” is still in the Borough High Street. It is a fine and flourishing remnant of an ancient galleried hostelry of the time of Chaucer, and it is characteristic of the continuity of English social, as well as political history that, although waggons and coaches no longer come to or set out from the “George,” its spacious yard is now a railway receiving-office for goods, where the railway vans, those descendants of the stage-waggon, thunderously come and go all day.

It will be observed that the traffic in those days went to and from Southwark, which was then the great business centre for the carriers. Not yet was the Brighton road measured from Westminster Bridge, for the adequate reason that there was no bridge at Westminster until 1749: only the ferry from the Horseferry Road to Lambeth.

Widow Smith’s waggon halted at Lewes, and it is not until ten years later than the date of her advertisement that we hear of the Brighthelmstone conveyance. The first was that announced by the pioneer, James Batchelor, in The Sussex Weekly Advertiser, May 12th, 1756:

NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that the LEWES ONE DAY STAGE COACH or CHAISE sets out from the Talbot Inn, in the Borough, on Saturday next, the 19th instant.

When likewise the Brighthelmstone Stage begins.

Performed (if God permit) by

JAMES BATCHELOR.

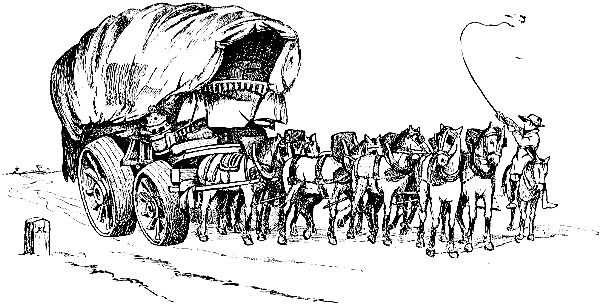

The “Talbot” inn, which stood on the site of the ancient “Tabard,” of Chaucerian renown, disappeared from the Borough High Street in 1870. What its picturesque yard was like in 1815, with the waggons of the Sussex carriers, let the illustration tell.

Let us halt awhile, to admire the courage of those coaching and waggoning pioneers who, in the days before “the sea-side” had been invented, and few people travelled, dared the awful roads for what must[Pg 15] then have been a precarious business. Sussex roads in especial had a most unenviable name for miriness, and wheeled traffic was so difficult that for many years after this period the farmers and others continued to take their womenkind about in the pillion fashion here caricatured by Henry Bunbury.

Horace Walpole, indeed, travelling in Sussex in 1749, visiting Arundel and Cowdray, acquired a too intimate acquaintance with their phenomenal depth of mud and ruts, inasmuch as he—finicking little gentleman—was compelled to alight precipitately from his overturned chaise, and to foot it like any common fellow. One quite pities his daintiness in the narration of his sorrows, picturesquely set forth by that accomplished letter-writer arrived home to the safe seclusion of Strawberry Hill. He writes to George Montagu, and dates August 26th, 1749:

“Mr. Chute and I returned from our expedition miraculously well, considering all our distresses. If you love good roads, conveniences, good inns, plenty of postilions and horses, be so kind as never to go into Sussex. We thought ourselves in the northest part of England; the whole county has a Saxon air, and the inhabitants are savage, as if King George the Second was the first monarch of the East Angles. Coaches grow there no more than balm and spices: we were forced to drop our post-chaise, that resembled nothing so much as harlequin’s calash, which was occasionally a chaise or a baker’s cart. We journeyed over alpine mountains” (Walpole, you will observe, was, equally with the evening journalist of these happy times, not unaccustomed to exaggerate) “drenched in clouds, and thought of harlequin again, when he was driving the chariot of the sun through the morning clouds, and was so glad to hear the aqua vitæ man crying a dram.... I have set up my staff, and finished my pilgrimages for this year. Sussex is a great damper of curiosity.”

Thus he prattles on, delightfully describing the peculiarities of the several places he visited with this[Pg 16] Mr. Chute, “whom,” says he, “I have created Strawberry King-at-Arms.” One wonders what that mute, inglorious Chute thought of it all; if he was as disgusted with Sussex sloughs and moist unpleasant “mountains” as his garrulous companion. Chute suffered in silence, for the sight of pen, ink, and paper did not induce in him a fury of composition; and so we shall never know what he endured.

Then the pedantic Doctor John Burton, who journeyed into Sussex in 1751, had no less unfortunate acquaintance with these miry ways than our dilettante of Strawberry Hill. To those who have small Latin and less Greek, this traveller’s tale must ever remain a sealed book; for it is in those languages that he records his views upon ways and means, and men and manners, in Sussex. As thus, for example:

“I fell immediately upon all that was most bad, upon a land desolate and muddy, whether inhabited by men or beasts a stranger could not easily distinguish, and upon roads which were, to explain concisely what is most abominable, Sussexian. No one would imagine them to be intended for the people and the public, but rather the byways of individuals, or, more truly, the tracks of cattle-drivers; for everywhere the usual footmarks of oxen appeared, and we too, who were on horseback, going along zigzag, almost like oxen at plough, advanced as if we were turning back, while we followed out all the twists of the roads.... My friend, I will set before you a kind of problem in the manner of Aristotle:—Why comes it that the oxen, the swine, the women, and all other animals(!) are so long-legged in Sussex? Can it be from the difficulty of pulling the feet out of so much mud by the strength of the ankle, so that the muscles become stretched, as it were, and the bones lengthened?”

A doleful tale. Presently he arrives at the conclusion that the peasantry “do not concern themselves with literature or philosophy, for they consider the pursuit of such things to be only idling,” which is not so very[Pg 17] remarkable a trait, after all, in the character of an agricultural people.

THE “TALBOT” INN YARD. BOROUGH, ABOUT 1815.

From an old drawing.

[Pg 18]Our author eventually, notwithstanding the terrible roads, arrived at Brighthelmstone, by way of Lewes, “just as day was fading.” It was, so he says, “a village on the sea-coast; lying in a valley gradually sloping, and yet deep. It is not, indeed, contemptible as to size, for it is thronged with people, though the inhabitants are mostly very needy and wretched in their mode of living, occupied in the employment of fishing, robust in their bodies, laborious, and skilled in all nautical crafts, and, as it is said, terrible cheats of the custom-house officers.” As who, indeed, is not, allowing the opportunity?

Batchelor, the pioneer of Brighton coaching, continued his enterprise in 1757, and with the coming of spring, and the drying of the roads, his coaches, which had been laid up in the winter, after the usual custom of those times, were plying again. In May he advertised, “for the convenience of country gentlemen, etc.,” his London, Lewes, and Brighthelmstone stage-coach, which performed the journey of fifty-eight miles in two days; and exclusive persons, who preferred to travel alone, might have post-chaises of him.

Brighthelmstone had in the meanwhile sprung into notice. The health-giving qualities of its sea air, and the then “strange new eccentricity” of sea-bathing, advocated from 1750 by Dr. Richard Russell, had already given it something of a vogue among wealthy invalids, and the growing traffic was worth competing for. Competitors therefore sprang up to share Batchelor’s business. Most of them merely added stage-coaches like his, but in May, 1762, a certain “J. Tubb,” in partnership with “S. Brawne,” started a very superior conveyance, going from London one day and returning from Brighthelmstone the next. This was the:

LEWES and BRIGHTELMSTONE new FLYING MACHINE (by Uckfield), hung on steel springs, very neat and commodious, to carry Four Passengers, sets out from the Golden Cross Inn, Charing Cross, on Monday, the 7th of June, at six o’clock in the morning, and will continue Monday’s, Wednesday’s, and Friday’s to the White Hart, at Lewes, and the Castle, at Brightelmstone, where regular Books are kept for entering passenger’s and parcels; will return to London Tuesday’s, Thursday’s, and Saturday’s Each Inside Passenger to Lewes, Thirteen Shillings; to Brighthelmstone, Sixteen; to be allowed Fourteen Pound Weight for Luggage, all above to pay One Penny per Pound; half the fare to be paid at Booking, the other at entering the machine. Children in Lap and Outside Passengers to pay half-price.

Performed by J. TUBB.

S. BRAWNE.

ME AND MY WIFE AND DAUGHTER.

From a caricature by Henry Bunbury.

[Pg 20]Batchelor saw with dismay this coach performing the whole journey in one day, while his took two. But he determined to be as good a man as his opponent, if not even a better, and started the next week, at identical fares, “a new large Flying Chariot, with a Box and four horses (by Chailey) to carry two Passengers only, except three should desire to go together.” The better to crush the presumptuous Tubb, he later on reduced his fares. Then ensued a diverting, if by no means edifying, war of advertisements; for Tubb, unwilling to be outdone, inserted the following in The Lewes Journal, November, 1762:

THIS IS TO INFORM THE PUBLIC that, on Monday, the 1st of November instant, the LEWES and BRIGHTHELMSTON FLYING MACHINE began going in one day, and continues twice a week during the Winter Season to Lewes only; sets out from the White Hart, at Lewes, Mondays and Thursdays at Six o’clock in the Morning, and returns from the Golden Cross, at Charing Cross, Tuesdays and Saturdays, at the same hour.

Performed by J. TUBB.

N.B.—Gentlemen, Ladies, and others, are desired to look narrowly into the Meanness and Design of the other Flying Machine to Lewes and Brighthelmston, in lowering his [Pg 21]prices, whether ’tis thro’ conscience or an endeavour to suppress me. If the former is the case, think how you have been used for a great number of years, when he engrossed the whole to himself, and kept you two days upon the road, going fifty miles. If the latter, and he should be lucky enough to succeed in it, judge whether he wont return to his old prices, when you cannot help yourselves, and use you as formerly. As I have, then, been the remover of this obstacle, which you have all granted by your great encouragement to me hitherto, I, therefore, hope for the continuance of your favours, which will entirely frustrate the deep-laid schemes of my great opponent, and lay a lasting obligation on,—Your very humble Servant,

J. TUBB.

To this replies Batchelor, possessed with an idea of vested interests pertaining to himself:

WHEREAS, Mr. Tubb, by an Advertisement in this paper of Monday last, has thought fit to cast some invidious Reflections upon me, in respect of the lowering my Prices and being two days upon the Road, with other low insinuations, I beg leave to submit the following matters to the calm Consideration of the Gentlemen, Ladies, and other Passengers, of what Degree soever, who have been pleased to favour me, viz.:

That our Family first set up the Stage Coach from London to Lewes, and have continued it for a long Series of Years, from Father to Son and other Branches of the same Race, and that even before the Turnpikes on the Lewes Road were erected they drove their Stage, in the Summer Season, in one day, and have continued to do ever since, and now in the Winter Season twice in the week. And it is likewise to be considered that many aged and infirm Persons, who did not chuse to rise early in the Morning, were very desirous to be two Days on the Road for their own Ease and Conveniency, therefore there was no obstacle to be removed. And as to lowering my prices, let every one judge whether, when an old Servant of the Country perceives an Endeavour to suppress and supplant him in his Business, he is not well justified in taking all measures in his Power for his own Security, and even to oppose an unfair Adversary as far as he can. ’Tis, therefore, [Pg 22]hoped that the descendants of your very ancient Servants will still meet with your farther Encouragement, and leave the Schemes of our little Opponent to their proper Deserts.—I am, Your old and present most obedient Servant,

J. BATCHELOR.

December 13, 1762.

The rivals both kept to the road until the death of Batchelor, in 1766, when his business was sold to Tubb, who took into partnership a Mr. Davis. Together they started, in 1767, the first service of a daily coach in the “Lewes and Brighthelmstone Flys,” each carrying four passengers, one to London and one to Brighton every day.

Tubb and Davis had in 1770 one “machine” and one waggon on this road, fare by “machine” 14s. The machine ran daily to and from London, starting at five o’clock in the morning. The waggon was three days on the road. Another machine was also running, but with the coming of winter these machines performed only three double journeys each a week.

In 1777 another stage-waggon was started by “Lashmar & Co.” It loitered between the “King’s Head,” Southwark, and the “King’s Head,” Brighton, starting from London every Tuesday at the unearthly hour of 3 a.m., and reaching its destination on Thursday afternoons.

On May 31st, 1784, Tubb and Davis put a “light post-coach” on the road, running to Brighton one day returning to London the next, in addition to their already running “machine” and “post-coach.” This new conveyance presumably made good time, four “insides” only being carried.

Four years later, when Brighton’s sun of splendour was rising, there were on the road between London and the sea three “machines,” three light post-coaches, two coaches, and two stage-waggons. Tubb now disappears, and his firm becomes Davis & Co. Other proprietors were Ibberson & Co., Bradford & Co., and Mr. Wesson.

[Pg 23]On May 1st, 1791, the first Brighton Mail coach was established. It was a two-horse affair, running by Lewes and East Grinstead, and taking twelve hours to perform the journey. It was not well supported by the public, and as the Post Office would not pay the contractors a higher mileage, it was at some uncertain period withdrawn.

About 1796 coach offices were opened in Brighton for the sole despatch of coaching business, the time having passed away for the old custom of starting from inns. Now, too, were different tales to tell of these roads, after the Pavilion had been set in course of building. Royalty and the Court could not endure to travel upon such evil tracks as had hitherto been the lot of travellers to Brighthelmstone. Presently, instead of a dearth of roads and a plethora of ruts, there became a choice of good highways and a plenty of travellers upon them.

Numerous coaches ran to meet the demands of the travelling public, and these continually increased in number and improved in speed. About this time first appear the firms of Henwood, Crossweller, Cuddington, Pockney & Harding, whose office was at No. 44, East Street: and Boulton, Tilt, Hicks, Baulcomb & Co., at No. 1, North Street. The most remarkable thing, to my mind, about those companies is their long-winded names. In addition to the old service, there ran a “night post-coach” on alternate nights, starting at 10 p.m. in the season. One then went to or from London generally in “about” eleven hours, if all went well. If you could afford only a ride in the stage-waggon, why then you were carried the distance by the accelerated (!) waggons of this line in two days and one night.

Erredge, the historian of Brighton, tells something of the social side of Brighton Road coaching at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Social indeed, as you shall see:

“In 1801 two pair-horse coaches ran between London and Brighton on alternate days, one up, the other down, driven by Messrs. Crossweller and Hine. The progress of these coaches was amusing. The one from London left the Blossoms Inn, Lawrence Lane, at 7 a.m., the passengers breaking their fast at the Cock, Sutton, at 9. The next stoppage for the purpose of refreshment was at the Tangier, Banstead Downs—a rural little spot, famous for its elderberry wine, which used to be brought from the cottage ‘roking hot,’ and on a cold wintry morning few refused to partake of it. George IV. invariably stopped here and took a glass from the hand of Miss Jeal as he sat in his carriage. The important business of luncheon took place at Reigate, where sufficient time was allowed the passengers to view the Baron’s Cave, where, it is said, the barons assembled the night previous to their meeting King John at Runymeade. The grand halt for dinner was made at Staplefield Common, celebrated for its famous black cherry-trees, under the branches of which, when the fruit was ripe, the coaches were allowed to draw up and the passengers to partake of its tempting produce. The hostess of the hostelry here was famed for her rabbit-puddings, which, hot, were always waiting the arrival of the coach, and to which the travellers never failed to do such ample justice, that ordinarily they found it quite impossible to leave at the hour appointed; so grogs, pipes, and ale were ordered in, and, to use the language of the fraternity, ‘not a wheel wagged’ for two hours. Handcross was a little resting-place, celebrated for its ‘neat’ liquors, the landlord of the inn standing, bottle in hand, at the door. He and several other bonifaces at Friars’ Oak, etc., had the reputation of[Pg 25] being on pretty good terms with the smugglers who carried on their operations with such audacity along the Sussex coast.

“After walking up Clayton Hill, a cup of tea was sometimes found to be necessary at Patcham, after which Brighton was safely reached at 7 p.m. It must be understood that it was the custom for the passengers to walk up all the hills, and even sometimes in heavy weather to give a push behind to assist the jaded horses.”

But it was not always so ideal or so idyllic. That there were discomforts and accidents is evident from the wordy warfare of advertisements that followed upon the starting of the Royal Brighton Four Horse Company in 1802. As a competitor with older firms, it seems to have aroused much jealousy and slander, if we may believe the following contemporary advertisement:

THE ROYAL BRIGHTON Four Horse Coach Company beg leave to return their sincere thanks to their Friends and the Public in general for the very liberal support they have experienced since the starting of their Coaches, and assure them it will always be their greatest study to have their Coaches safe, with good Horses and sober careful Coachmen.

They likewise wish to rectify a report in circulation of their Coach having been overturned on Monday last, by which a gentleman’s leg was broken, &c., no such thing having ever happened to either of their Coaches. The Fact is it was one of the Blue Coaches instead of the Royal New Coach.

⁂ As several mistakes have happened, of their friends being BOOKED at other Coach offices, they are requested to book themselves at the ROYAL NEW COACH OFFICE, CATHERINE’S HEAD, 47, East Street.

The coaching business grew rapidly, and in an advertisement offering for sale a portion of the coaching business at No. 1, North Street, it was stated that the annual returns of this firm were more than £12,000 per annum, yielding from Christmas, 1794, to[Pg 26] Christmas, 1808, seven and a half per cent. on the capital invested, besides purchasing the interest of four of the partners in the concern. In this last year two new businesses were started, those of Waldegrave & Co., and Pattenden & Co. Fares now ruled high—23s. inside; 13s. outside.

The year 1809 marked the beginning of a new and strenuous coaching era on this road. Then Crossweller & Co. commenced to run their “morning and night” coaches, and William “Miller” Bradford formed his company. This was an association of twelve members, contributing £100 each, for the purpose of establishing a “double” coach—that is to say, one up and one down, each day. The idea was to “lick creation” on the Brighton Road by accelerating the speed, and to this end they acquired some forty-five horses then sold out of the Inniskilling Dragoons, at that time stationed at Brighton. On May Day, 1810, the Brighton Mail was re-established. These “Royal Night Mail Coaches” as they were grandiloquently announced, were started by arrangement with the Postmaster-General. The speed, although much improved, was not yet so very great, eight hours being occupied on the way, although these coaches went by what was then the new cut via Croydon. Like the Dover. Hastings, and Portsmouth mails, the Brighton Mail was two-horsed. It ran to and from the “Blossoms” Inn, Lawrence Lane, Cheapside, and never attained a better performance than 7 hours 20 minutes, a speed of 7½ miles an hour. It had, however, this distinction, if it may so be called: it was the slowest mail in the kingdom.

It was on June 25th, 1810, that an accident befell Waldegrave’s “Accommodation” coach on its up journey. Near Brixton Causeway its hind wheels collapsed, owing to the heavy weight of the loaded vehicle. By one of those strange chances when truth appears stranger than fiction, there chanced to be a farmer’s waggon passing the coach at the instant of its overturning. Into it were shot the “outsiders,”[Pg 27] fortunate in this comparatively easy fall. Still, shocks and bruises were not few, and one gentleman had his thigh broken.

By June, 1811, traffic had so increased that there were then no fewer than twenty-eight coaches running between Brighton and London. On February 5th in the following year occurred the only great road robbery known on this road. This was the theft from the “Blue” coach of a package of bank-notes representing a sum of between three and four thousand pounds sterling. Crosswellers were proprietors of the coach, and from them Messrs. Brown, Lashmar & West, of the Brighton Union Bank, had hired a box beneath the seat for the conveyance of remittances to and from London. On this day the Bank’s London correspondents placed these notes in the box for transmission to London, but on arrival the box was found to have been broken open and the notes all stolen. It would seem that a carefully planned conspiracy had been entered into by several persons, who must have had a thorough knowledge of the means by which the Union Bank sent and received money to and from the metropolis. On this morning six persons were booked for inside places. Of this number two only made an appearance—a gentleman and a lady. Two gentlemen were picked up as the coach proceeded. The lady was taken suddenly ill when Sutton was reached, and she and her husband were left at the inn there. When the coach arrived at Reigate the two remaining passengers went to inquire for a friend. Returning shortly, they told the coachman that the friend whom they had supposed to be at Brighton had returned to town, therefore it was of no use proceeding further.

Thus the coachman and guard had the remainder of the journey to themselves, while the cash-box, as was discovered at the journey’s end, was minus its cash. A reward of £300 was immediately offered for information that would lead to recovery of the notes. This was subsequently altered to an offer of 100 guineas[Pg 28] for information of the offender, in addition to £300 upon recovery of the total amount, or “ten per cent. upon the amount of so much thereof as shall be recovered.” No reward money was ever paid, for the notes were never recovered, and the thieves escaped with their booty.

In 1813 the “Defiance” was started, to run to and from Brighton and London in the daytime, each way six hours. This produced the rival “Eclipse,” which belied the suggestion of its name and did not eclipse, but only equalled, the performance of its model. But competition had now grown very severe, and fares in consequence were reduced to—inside, ten shillings; outside, five shillings. Indeed, in 1816, a number of Jews started a coach to run from London to Brighton in six hours: or, failing to keep time, to forfeit all fares. Needless to say, under such Hebrew management, and with that liability, it was punctuality itself; but Nemesis awaited it, in the shape of an information laid for furious driving.

The Mail, meanwhile, maintained its ancient pace of a little over six miles an hour—a dignified, no-hurry, governmental rate of progression. There was, in fact, no need for the Brighton Mail to make speed, for the road from the General Post Office is only fifty-three miles in length, and all the night and the early morning, from eight o’clock until five or six o’clock a.m., lay before it.

We come now to the “Era of the Amateur,” who not only flourished pre-eminently on the Brighton Road, but may be said to have originated on it. The coaching amateur and the nineteenth century came into existence almost contemporaneously. Very soon after 1800 it became “the thing” to drive a coach, and shortly after this became such a definite ambition, there arose[Pg 29] that contradiction in terms, that horsey paradox, the Amateur Professional, generally a sporting gentleman brought to utter ruin by Corinthian gambols, and taking to the one trade on earth at which he could earn a wage. That is why the Golden Age of coaching won on the Brighton Road a refinement it only aped elsewhere.

It is curious to see how coaching has always been, even in its serious days, before steam was thought of, the chosen amusement of wealthy and aristocratic whips. Of those who affected the Brighton Road may be mentioned the Marquis of Worcester, who drove the “Duke of Beaufort,” Sir St. Vincent Cotton of the “Age,” and the Hon. Fred Jerningham, who drove the Day Mail. The “Age,” too, had been driven by Mr. Stevenson, a gentleman and a graduate of Cambridge, whose “passion for the bench,” as “Nimrod” says, superseded all other worldly ambitions. He became a coachman by profession, and a good professional he made; but he had not forgotten his education and early training, and he was, as a whip, singularly refined and courteous. He caused, at a certain change of horses on the road, a silver sandwich-box to be handed round to the passengers by his servant, with an offer of a glass of sherry, should any desire one. Another gentleman, “connected with the first families in Wales,” whose father long represented his native county in Parliament, horsed and drove one side of this ground with Mr. Stevenson.

This was “Sackie,” Sackville Frederick Gwynne, of Carmarthenshire, who quarrelled with his relatives and took to the road; became part proprietor of the “Age,” broke off from Stevenson, and eventually lived and died at Liverpool as a cabdriver. He drove a cab till 1874, when he died, aged seventy-three.

Harry Stevenson’s connection with the Brighton Road began in 1827, when, as a young man fresh from Cambridge, he brought with him such a social atmosphere and such full-fledged expertness in driving[Pg 30] a coach that Cripps, a coachmaster of Brighton and proprietor of the “Coronet,” not only was overjoyed to have him on the box, but went so far as to paint his name on the coach as one of the licensees, for which false declaration Cripps was fined in November, 1827.

The parentage and circumstances of Harry Stevenson are alike mysterious. We are told that he “went the pace,” and was already penniless at twenty-two years of age, about the time of his advent upon the Brighton Road. In 1828 his famous “Age” was put on the road, built for him by Aldebert, the foremost coach-builder of the period, and appointed in every way with unexampled luxury. The gold- and silver-embroidered horse-cloths of the “Age” are very properly preserved in the Brighton Museum. Stevenson’s career was short, for he died in February, 1830.

Coaching authorities give the palm for artistry to whips of other roads: they considered the excellence of this as fatal to the production of those qualities that went to make an historic name. This road had become “perhaps the most nearly perfect, and certainly the most fashionable, of all.”

With the introduction of this sporting and irresponsible element, racing between rival coaches—and not the mere conveying of passengers—became the real interest of the coachmen, and proprietors were obliged to issue notices to assure the timid that this form of rivalry would be discouraged. A slow coach, the “Life Preserver,” was even put on the road to win the support of old ladies and the timid, who, as the record of accidents tells us, did well to be timorous. But accidents would happen to fast and slow alike. The “Coburg” was upset at Cuckfield in August, 1819. Six of the passengers were so much injured that they could not proceed, and one died the following day at the “King’s Head.” The “Coburg” was an old-fashioned coach, heavy, clumsy, and slow, carrying six passengers inside and twelve outside. This type gave place to coaches of lighter build about 1823.

THE “DUKE OF BEAUFORT” COACH STARTING FROM THE

“BULL AND MOUTH” OFFICE, PICCADILLY CIRCUS, 1826.

From an aquatint after W. J. Shayer.

[Pg 33]In 1826 seventeen coaches ran to Brighton from London every morning, afternoon, or evening. They had all of them the most high-sounding of names, calculated to impress the mind either with a sense of swiftness, or to awe the understanding with visions of aristocratic and court-like grandeur. As for the times they individually made, and for the inns from which they started, you who are insatiable of dry bones of fact may go to the Library of the British Museum and find your Cary (without an “e”) and do your gnawing of them. That they started at all manner of hours, even the most uncanny, you must rest assured; and that they took off from the (to ourselves) most impossible and romantic-sounding of inns, may be granted, when such examples as the strangely incongruous “George and Blue Boar,” the Herrick-like “Blossoms” Inn, and the idyllic-seeming “Flower-pot” are mentioned.

They were, those seventeen coaches, the “Royal Mail,” the “Coronet,” “Magnet,” “Comet,” “Royal Sussex,” “Sovereign,” “Alert,” “Dart,” “Union,” “Regent,” “Times,” “Duke of York,” “Royal George,” “True Blue,” “Patriot,” “Post,” and the “Summer Coach,” so called, and they nearly all started from the City and Holborn, calling at West End booking-offices on their several ways. Most of the old inns from which they set out are pulled down, and the memory of them has faded.

The “Golden Cross” at Charing Cross, from whose doors started the “Comet” and the “Regent” in this year of grace 1826, and at which the “Times” called on its way from Holborn, has been wholly remodelled; the “White Horse,” Fetter Lane, whence the “Duke of York” bowled away, has been demolished; the “Old Bell and Crown” Inn, Holborn, where the “Alert,” the “Union,” and the “Times” drew up daily in the old-fashioned galleried courtyard, is swept away. Were Viator to return to-morrow, he[Pg 34] would surely want to return to Hades, or Paradise, wherever he may be, at once. Around him would be, to his senses, an astonishing whirl and noise of traffic, despite the wood-paving that has superseded macadam, which itself displaced the granite setts he knew. Many strange and horrid portents he would note, and Holborn would be to him as an unknown street in a strange town.

Than 1826 the informative Cary goes no further, and his “Itinerary,” excellent though it be, and invaluable to those who would know aught of the coaches that plied in the years when it was published, gives no particulars of the many “butterfly” coaches and amateur drags that cut in upon the regular coaches during the rush and scour of the season.

In 1821 it was computed that over forty coaches ran to and from London and Brighton daily; in September, 1822, there were thirty-nine. In 1828 it was calculated that the sixteen permanent coaches then running, summer and winter, received between them a sum of £60,000 per annum, and the total sum expended in fares upon coaching on this road was taken as amounting to £100,000 per annum. That leaves the very respectable amount of £40,000 for the season’s takings of the “butterflies.”

An accident happened to the “Alert” on October 9th, 1829, when the coach was taking up passengers at Brighton. The horses ran away, and dashed the coach and themselves into an area sixteen feet deep. The coach was battered almost to pieces, and one lady was seriously injured. The horses escaped unhurt. In 1832, August 25th, the Brighton Mail was upset near Reigate, the coachman being killed.

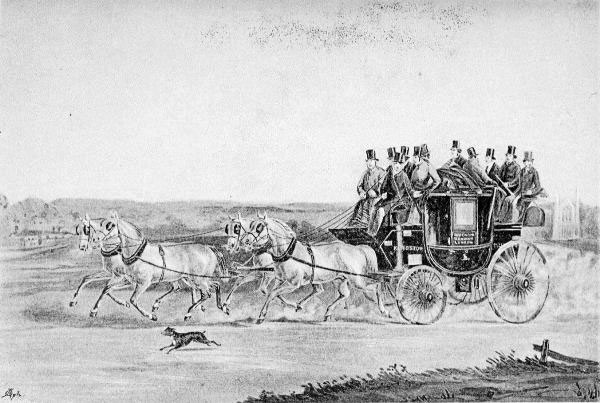

THE “AGE,” 1829, STARTING FROM CASTLE SQUARE, BRIGHTON.

From an engraving after C. Cooper Henderson.

[Pg 37]This was the era of those early motor-cars, the steam-carriages, which, in spite of their clumsy construction and appalling ugliness, arrived very nearly to a commercial success. Many inventors were engaged from 1823 to 1838 upon this subject. Walter Hancock, in particular, began in 1824, and in 1828 proposed a service of his “land-steamers” between London and Brighton, but did not actually appear upon this road with his “Infant” until November, 1832. The contrivance performed the double journey with some difficulty and in slower time than the coaches: but Hancock on that eventful day confidently declared that he was perfecting a newer machine by which he expected to run down in three and a half hours. He never achieved so much, but in October, 1833, his “Autopsy,” which had been successfully running as an omnibus between Paddington and Stratford, went from the works at Stratford to Brighton in eight and a half hours, of which three hours were taken up by a halt on the road.

No artist has preserved a view of this event for us, but a print may still be met with depicting the start of Sir Charles Dance’s steam-carriage from Wellington Street, Strand, for Brighton on some eventful morning of that same year. A prison-van is, by comparison with this fearsome object, a thing of beauty; but in the picture you will observe enthusiasm on foot and on horseback, and even four-legged, in the person of the inevitable dog. In the distance the discerning may observe the old toll-house on Waterloo Bridge, and the gaunt shape of the Shot Tower.

By 1839 the coaching business had in Brighton become concentrated in Castle Square, six of the seven principal offices being situated there. Five London coaches ran from the Blue Office (Strevens & Co.), five from the Red Office (Mr. Goodman’s), four from the “Spread Eagle” (Chaplin & Crunden’s), three from the Age (T. W. Capps & Co.), two from Hine’s, East Street; two from Snow’s (Capps & Chaplin), and two from the “Globe” (Mr. Vaughan’s).

To state the number of visitors to Brighton on a certain day will give an idea of how well this road was used during the decade that preceded the coming of steam. On Friday, October 25th, 1833, upwards of 480 persons travelled to Brighton by stage-coach. A comparison of this number with the hordes of visitors cast forth from the Brighton Railway Station[Pg 38] to-day would render insignificant indeed that little crowd of 1833; but in those times, when the itch of excursionising was not so acute as now, that day’s return was remarkable; it was a day that fully justified the note made of it. Then, too, those few hundreds benefited the town more certainly than perhaps their number multiplied by ten does now. For the Brighton visitor of a hundred years ago, once set down in Castle Square, had to remain the night at least in Brighton; for him there was no returning to London the same day. And so the Brighton folks had their wicked will of him for a while, and made something out of him; while in these times the greater proportion of a day’s excursionists find themselves either at home in London already, when evening hours are striking from Westminster Ben, or else waiting with what patience they may the collecting of tickets at the bleak and dismal penitentiary platforms of Grosvenor Road Station; and, after all, Brighton is little or nothing advantaged by their visit.

But though the tripper of the coaching era found it impracticable to have his morning in London, his day upon the King’s Road, and his evening in town again, yet the pace at which the coaches went in the ’30’s was by no means despicable. Ten miles an hour now became slow and altogether behind the age.

In 1833 the Marquis of Worcester, together with a Mr. Alexander, put three coaches on the road: an up and down “Quicksilver” and a single coach, the “Wonder.” The “Quicksilver,” named probably in allusion to its swiftness (it was timed for four hours and three-quarters), ran to and from what was then a favourite stopping-place, the “Elephant and Castle.” But on July 15th of the same year an accident, by which several persons were very seriously injured, happened to the up “Quicksilver” when starting from Brighton. Snow, who was driving, could not hold the team in, and they bolted away, and brought up violently against the railings by the New Steyne. Broken arms, fractured arms and ribs, and contusions were plenty. The “Quicksilver,” chameleon-like, changed colour after this mishap, was repainted and renamed, and reappeared as the “Criterion”; for the old name carried with it too great a spice of danger for the timorous.

SIR CHARLES DANCE’S STEAM-CARRIAGE LEAVING LONDON FOR BRIGHTON, 1833.

From a print after G. E. Madeley.

[Pg 41]On February 4th, 1834, the “Criterion,” driven by Charles Harbour, outstripping the old performances of the “Vivid,” and beating the previous wonderfully quick journey of the “Red Rover,” carried down King William’s Speech on the opening of Parliament in 3 hours and 40 minutes, a coach record that has not been surpassed, nor quite equalled, on this road, not even by Selby on his great drive of July 13th, 1888, his times being out and in respectively, 3 hours 56 minutes, and 3 hours 54 minutes. Then again, on another road, on May Day, 1830, the “Independent Tally-ho,” running from London to Birmingham, covered those 109 miles in 7 hours 39 minutes, a better record than Selby’s London to Brighton and back drive by eleven minutes, with an additional mile to the course. Another coach, the “Original Tally-ho,” did the same distance in 7 hours 50 minutes. The “Criterion” fared ill under its new name, and gained an unenviable notoriety on June 7th, 1834, being overturned in a collision with a dray in the Borough. Many of the passengers were injured; Sir William Cosway, who was climbing over the roof when the collision occurred, was killed.

In 1839, the coaching era, full-blown even to decay, began to pewk and wither before the coming of steam, long heralded and now but too sure. The tale of coaches now decreased to twenty-three; fares, which had fallen in the cut-throat competition of coach proprietors with their fellows in previous years to 10s. inside, 5s. outside for the single journey, now rose to 21s. and 12s. Every man that horsed a coach, seeing now was the shearing time for the public, ere the now building railway was opened, strove to make as much as possible ere he closed his yards, sold his stock, broke his coach up for firewood, and took himself off the road.

[Pg 42]Sentiment hung round the expiring age of coaching, and has cast a halo on old-time ways of travelling, so that we often fail to note the disadvantages and discomforts endured in those days; but, amid regrets which were often simply maudlin, occur now and again witticisms true and tersely epigrammatic, as thus:

For the neat wayside inn and a dish of cold meat

You’ve a gorgeous saloon, but there’s nothing to eat;

and a contributor to the Sporting Magazine observes, very happily, that “even in a ‘case’ in a coach, it’s ‘there you are’; whereas in a railway carriage it’s ‘where are you?’” in case of an accident.

On September 21st, 1841, the Brighton Railway was opened throughout, from London to Brighton, and with that event the coaching era for this road virtually died. Professional coach proprietors who wished to retain the competencies they had accumulated were well advised to shun all competition with steam, and others had been wise enough to cut their losses; for the Road for the next sixty years was to become a discarded institution and the Rail was entering into a long and undisputed possession of the carrying trade.

The Brighton Mail, however—or mails, for Chaplin had started a Day Mail in 1838—continued a few months longer. The Day Mail ceased in October, 1841, but the Night Mail held the road until March, 1842.

Between 1841, when the railway was opened all the way from London, and 1866, during a period of twenty-five years, coaching, if not dead, at least showed but few and intermittent signs of life. The “Age,” which then was owned by Mr. F. W. Capps, was the last coach to run regularly on the direct road to and from London. The “Victoria,” however, was on the road, via Dorking and Horsham, until November 8th, 1845.

The BRIGHTON DAY MAILS CROSSING HOOKWOOD COMMON, 1838.

From an engraving after W. J. Shayer.

[Pg 45]The “Age” had been one of the best equipped and driven of all the smart drags in that period when aristocratic amateur dragsmen frequented this road, when the Marquis of Worcester drove the “Beaufort,” and when the Hon. Fred Jerningham, a son of the Earl of Stafford, a whip of consummate skill, drove the day-mail; a time when the “Age” itself was driven by that sportsman of gambling memory, Sir St. Vincent Cotton, and by that Mr. Stevenson who was its founder, mentioned more particularly on page 37. When Mr. Capps became proprietor, he had as coachman several distinguished men. For twelve years, for instance, Robert Brackenbury drove the “Age” for the nominal pay of twelve shillings per week, enough to keep him in whips. It was thus supremely fitting that it should also have been the last to survive.

In later years, about 1852, a revived “Age,” owned and driven by the Duke of Beaufort and George Clark, the “Old” Clark of coaching acquaintance, was on the road to London, via Dorking and Kingston, in the summer months. It was discontinued in 1862. A picture of this coach crossing Ham Common en route for Brighton was painted in 1852 and engraved. A reproduction of it is shown here.

From 1862 to 1866 the rattle of the bars and the sound of the guard’s yard of tin were silent on every route to Brighton; but in the latter year of horsey memory and the coaching revival, a number of aristocratic and wealthy amateurs of the whip, among whom were representatives of the best coaching talent of the day, subscribed a capital, in shares of £10, and a little yellow coach, the “Old Times,” was put on the highway. Among the promoters of the venture were Captain Haworth, the Duke of Beaufort, Lord H. Thynne, Mr. Chandos Pole, Mr. “Cherry” Angell, Colonel Armytage, Captain Lawrie, and Mr. Fitzgerald. The experiment proved unsuccessful, but in the[Pg 46] following season, commencing in April, 1867, when the goodwill and a large portion of the stock had been purchased from the original subscribers, by the Duke of Beaufort, Mr. E. S. Chandos Pole, and Mr. Angell, the coach was doubled, and two new coaches built by Holland & Holland.

The Duke of Beaufort was chief among the sportsmen who horsed the coaches during this season. Mr. Chandos Pole, at the close of the summer season, determined to carry on by himself, throughout the winter, a service of one coach. This he did, and, aided by Mr. Pole-Gell, doubled it the next summer.

The following year, 1869, the coach had so prosperous a season that it showed never a clean bill, i.e., never ran empty, all the summer, either way. The partners this year were the Earl of Londesborough, Mr. Pole-Gell, Colonel Stracey Clitherow, Mr. Chandos Pole, and Mr. G. Meek.

From this season coaching became extremely popular on the Brighton Road, Mr. Chandos Pole running his coach until 1872. In the following year an American amateur, Mr. Tiffany, kept up the tradition with two coaches. Late in the season of 1874 Captain Haworth put in an appearance.

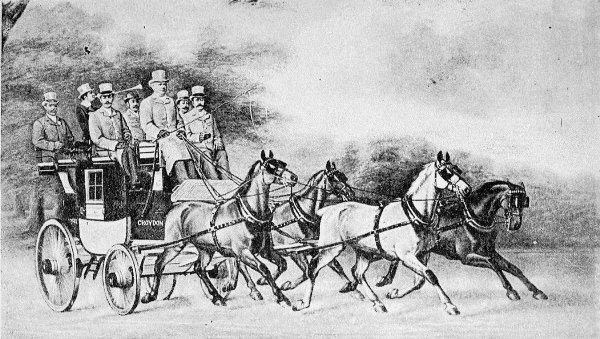

In 1875 the “Age” was put upon the road by Mr. Stewart Freeman, and ran in the season up to and including 1880, in which year it was doubled. Captain Blyth had the “Defiance” on the road to Brighton this year by the circuitous route of Tunbridge Wells. In 1881 Mr. Freeman’s coach was absent from the road, but Edwin Fownes put the “Age” on, late in the season. In the following year Mr. Freeman’s coach ran, doubled again, and single in 1883. It was again absent in 1884-5-6, in which last year it ran to Windsor; but it reappeared on the Brighton Road in 1887 as the “Comet,” and in the winter of that year was continued by Captain Beckett, who had Selby and Fownes as whips. In 1888 Mr. Freeman ran in partnership with Colonel Stracey-Clitherow, Lord Wiltshire, and Mr. Hugh M’Calmont, and in 1889 became partner in an undertaking to run the coach doubled. The two “Comets” therefore served the road in this season supported by two additional subscribers, the Honourable H. Sandys and Mr. Randolph Wemyss.

THE “AGE,” 1852, CROSSING HAM COMMON.

From an engraving after C. Cooper Henderson.

[Pg 49]In 1888 the “Old Times,” forsaking the Oatlands Park drive, had appeared on the Brighton Road as a rival to the “Comet,” and continued throughout the winter months, until Selby met his death in that winter.

The “Comet” ran single in the winter season of 1889-90, and in April was again doubled for the summer, running single in 1891-2-3, when Mr. Freeman relinquished it.

Mention has already been made of the “Old Times,” which made such a fleeting appearance on this road; but justice was not done to it, or to Selby, in that incidental allusion. They require a niche to themselves in the history of the revival—a niche to which shall be appended this poetic excerpt:

Here’s the “Old Times,” it’s one of the best,

Which no coaching man will deny,

Fifty miles down the road with a jolly good load,

Between London and Brighton each day.

Beckett, M’Adam, and Dickey, the driver, are there,

Of old Jim’s presence every one is aware,

They are all nailing good sorts,

And go in for all sports,

So we’ll all go a-coaching to-day.

It is poetry whose like we do not often meet. Tennyson himself never attempted to capture such heights of rhyme. He could, and did, rhyme “poet” with “know it,” but he never drove such a Cockney team as “deny” and “to-dy” to water at the Pierian springs.

“Carriages without horses shall go,” is the “prophecy” attributed to that mythical fifteenth century pythoness, Mother Shipton; really the ex post facto forgery of Charles Hindley, the second-hand bookseller, in 1862. It should not be difficult, on such terms, to earn the reputation of a seer.

Between 1823 and 1838, the era of the steam-carriages, that prognostication had already been fulfilled: and again, in another sense, with the introduction of railways. But it was not until the close of 1896 that the real horseless era began to dawn. Railways, extravagantly discriminative tolls, and restrictions upon weight and speed killed the steam-carriages, and for more than fifty years the highways knew no other mechanical locomotion than that of the familiar traction-engines, restricted to three miles an hour and preceded by a man with a red flag. It is true that a few hardy inventors continued to waste their time and money on devising new forms of steam-carriages, and were only fined for their pains when they were rash enough to venture on the public roads, as when Bateman, of Greenwich, invented a steam-tricycle, and Sir Thomas Parkyn, Bart., was fined at Greenwich Police Court, April 8th, 1881, for riding it.

That incident appears to have finally quenched the ardour of inventive genius in this country; but a new locomotive force already existing unsuspected was about this period being experimented with on the Continent by one Gottlieb Daimler, whose name—generally mispronounced—is now sufficiently familiar to all who know anything of motor-cars.

Daimler was at that time connected with the Otto Gas Engine Works in Germany, where the adaptive Germans were exploiting the gas-engine principle invented by Crossley many years before.

In 1886 Daimler produced his motor-bicycle, and by 1891 his motor engine was adapted by Panhard and Levassor to other types of vehicles. The French were thus the first to perceive the great possibilities of it, and by 1894 the motor-cars already in use in France were so numerous that the first sporting event in the history of them—the 760 miles’ race from Paris to Bordeaux and back—was run.

THE “OLD TIMES,” 1888.

From a painting by Alfred S. Bishop.